A journal for industry and audiences covering the past, present, and future of the musical stage.

Dear Mr. Kaufman:

The opinion piece you penned for American Theatre magazine – “How Buena Vista Social Club Expands the Language of the Musical” – is built upon factual inaccuracies and common misperceptions concerning the legitimate musical stage. While I seek in no way to diminish your evident love of the musical in question or your admiration for the artists who created it, I feel compelled to address, publicly, your negligent, or theatrically ignorant, statements about its position in the history of the established art form of which it is a part, because context is crucial, and because an accurate representation and a rigorous, practical understanding of the art form’s evolution, and especially its maturation in the middle of the 20th century, is critical to the creation of new works – imbued with contemporary subjects, themes, and musical languages – that realize the possibilities of professionalism and excellence in musical storytelling.

“There are shows in the history of the American musical that don’t just entertain but redefine the form”

Let us be clear: the musical theatre is a singular art form, but not all musicals take a single form (i.e. shape). Thus, I am unclear on what you mean by “redefine the form,” and your three ensuing examples do not help to clarify.

“Oklahoma! introduced the idea that song, story, and dance could be seamlessly integrated into a cohesive narrative”

Oklahoma! (1943) was an incontrovertible landmark, but it did not introduce the idea of seamless integration – which was a central component of the theatrical movement, begun about the 1910s and brought to a close in the 1960s, to better the art of musical storytelling. This movement, experimental in nature, similarly involved advancements in craft, developments in character and composition, and explorations in subject-matter and theme, and it resulted in the maturation of the legitimate musical stage in the middle of the 20th century. And, though rarely discussed or even acknowledged today, this movement was clearly and exhaustively documented in the words and works of numerous artists.

One of the most pronounced was surely book writer and lyricist Oscar Hammerstein II, whose stylistically diverse work, in the two decades prior to the creation of Oklahoma!, included Always You (1920), Mary Jane McKane (1923), Music in the Air (1932), and Show Boat (1927), a monumental and remarkably mature drama that has been erroneously referred to as the first book musical, and the first integrated book musical. Rainbow (1928), in particular, contained an interlude for the leading man entitled “Soliloquy,” Sunny River (1941) contained a “Pictorial Overture” played in pantomime, and Rose-Marie (1924) contained a scene of adultery and murder played in pantomime, and it refrained from printing in its program a formal song list, printing instead an authors’ note, which read, “The musical numbers in this play are such an integral part of the action that we do not think we should list them as separate episodes.”

In 1924, shortly after the opening of Rose-Marie, Hammerstein wrote, in part: “The first thing to realize is that a good musical comedy book must not necessarily be a good play. Indeed, to take a good play and set it to music usually will ruin both the music and the play. A good libretto is a mixture of dialogue and lyrics scientifically constructed so as to build up to musical high spots, to provide opportunity for special entertainment, and at the same time make each moment of entertainment bear its own significance to the plot. The most tiresome type of musical play is the kind in which there is a definite cleavage between dialogue and lyrics – where the spoken words carry the story and the words that are sung come in as interpolated episodes of extraneous entertainment.”

Rose-Marie was, not coincidentally, coauthored by book writer and lyricist Otto Harbach, who served as Hammerstein’s mentor, and who collaborated with the young talent on shows such as The Desert Song (1926), Golden Dawn (1927), Sunny (1925), and Wildflower (1923). Harbach, who observed in the mid 1920s that the public was demanding “a solid dramatic foundation for musical comedy,” separately collaborated with Frank Mandel, Irving Caesar, and Vincent Youmans on the landmark musical comedy No, No, Nanette (1925), whose 1971 adaptation, by Burt Shevelove, of A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum (1962), remains a part of the permanent repertory. In the late 1920s, Harbach wrote, in part, “In my twenty years of experience, I have not found the writing of musical plays as simple a matter as it is commonly supposed to be. My fond notion that they consist merely of lively folderol insouciantly strung together and interrupted from time to time by musical numbers, was rudely shattered when I came to realize that ‘gags’ and glitter are only accessories to the Main Thing – which is a logical, well built play that lends itself effectively to musical highlighting, so that each number may explain a character or crystallize a dramatic situation.”

Other early exponents of the decades-long movement to better the art of musical storytelling include book writer James Montgomery, of Irene (1919) and Oh, Look! (1918), who believed in “real books” and “true to life” characters, and book writer and lyricist Harlan Thompson, of Little Jessie James (1923), Merry, Merry (1925), and My Girl (1924), who believed that “the book should be the backbone of the show,” and that “humor should be the outgrowth of character and situation.” All three shows had music by Harry Archer, and Little Jessie James, in particular, employed a small cast, a single set, and an eleven-piece jazz band, in place of the traditional orchestra, whose members were reportedly handpicked by Paul Whiteman and introduced, one-by-one, during the overture.

Meanwhile, in the late 1920s and 1930s, Lorenz Hart and Richard Rodgers made major contributions to the movement with musicals like The Boys from Syracuse (1938) and On Your Toes (1936). “We write for situation,” Rodgers explained. “We try to adapt the words and music to the requirements of the characters and circumstances laid down for us by the book.” The Boys from Syracuse and On Your Toes were coauthored and directed by George Abbott, a master of comedy and farce who had an inclination toward modern-minded material, and, as he proposed late in his lengthy career, “a great influence on writing musicals that made sense.” Abbott’s singular brand of stagecraft, imbued with a fast pace and crisp action, has been described by author and director Garson Kanin as a combination of “innocence and sophistication, formal structure and daring innovation,” and it was firmly rooted in honesty. As Brooks Atkinson, a long-time critic for The New York Times, observed, “Although the characters are behaving like headstrong imbeciles, they are desperately serious. Every moment in the performance is a crisis for one or the other of them. No matter how boisterously the audience may be laughing, the characters never intimate that the rumpus in which they are involved is crackbrained and ludicrous and a travesty on the life the audience thinks it is living outside the theatre.”

Abbott, Hart, and Rodgers also collaborated on Jumbo (1935), Too Many Girls (1939), and Pal Joey (1940), which closed its first act with a dream ballet. The original production was choreographed by Robert Alton, a pioneering dance director who, in 1941, explained, “My idea is not to break up the show but to make the dances part of the show – make them carry the plot forward.”

One of Hart and Rodgers’ most intriguing and adventurous properties was Peggy-Ann (1926), an intimate musical comedy that unfolded primarily as a series of dream sequences inside the mind of its central figure. Arthur Schwartz, the composer of The Band Wagon (1931) and A Tree Grows in Brooklyn (1951), worked on the unusually patterned piece as a rehearsal pianist, and he described it decades later as “innovative,” noting, “It had an integrated score, using songs to advance action and describe character, rather than to be placed extraneously for their own sakes.” Peggy-Ann had a book by Herbert Fields, and the musical opted out of an opening chorus and a big finish. “Imagine closing a show with a whisper and a laugh,” choreographer Seymour Felix remarked at the time. “That is how Peggy-Ann ends.”

Other offerings that sought, prior to 1943, to fuse dialogue, song, and dance into a single theatrical statement for the express purpose of telling a single theatrical tale include, but are not limited to, Of Thee I Sing (1931), Knickerbocker Holiday (1938), and Lady in the Dark (1941). Of the latter, book writer Moss Hart, in 1941, proposed that the lyrics and music are “part and parcel of the basic structure of the play,” and that they “carry the story forward dramatically and psychologically.”

And this is to say nothing of original revue – a distinct, dynamic, and often exhilarating form, of musical theatre, that had neither a story nor a plot, but consisted of individual comedy sketches, songs, and dances organized into a specific routine and created expressly for the occasion. Revue had, between roughly the 1920s and the 1940s, a tremendous impact on the character, methods, and mechanics of the maturing book, or story-driven, musical, and several artists, like sketch writer and lyricist Howard Dietz, sought to make the script of a revue “as complete as that of a play.”

“Company shattered the expected structure of musical storytelling”

Company (1970) is an extraordinarily well written work, but what “expected structure” did it shatter? And what, furthermore, is “the classical musical theatre form” from which you suggest Buena Vista Social Club makes “a seismic departure?”

There is simply no one way to make a musical, nor is there a limit to the stories one can tell on the musical stage, though there remains an art to musical storytelling, a rigorous creative science, which is not to be confused with the nonexistent rules of musical theatre; and the middle of the 20th century, along with the decades prior, was defined by no one story, no one sound, no one artist, and no one show. Nor was it defined by a single, expected structure or classical musical theatre form.

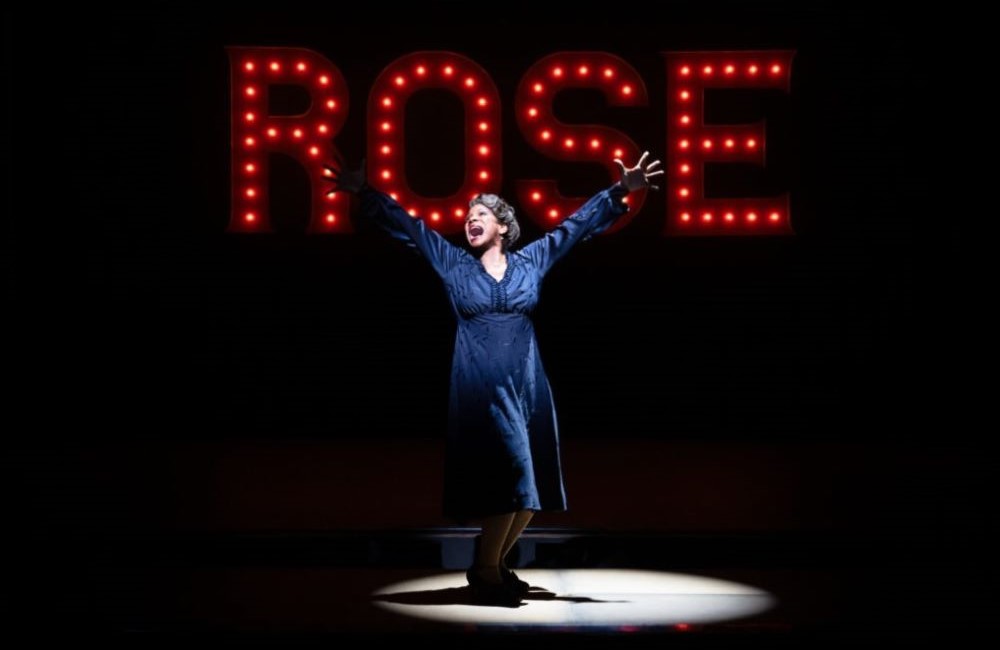

Take, for instance, Guys and Dolls (1950) and My Fair Lady (1956). Do these two topflight entertainments operate in the same manner? Do Carousel (1945) and Top Banana (1951)? Wonderful Town (1953) and Cabaret (1966)? The Cradle Will Rock (1937) and Carmen Jones (1943)? Hello, Dolly! (1964) and Kiss Me, Kate (1948)? West Side Story (1957) and The King and I (1951)? The Pajama Game (1954) and Lady in the Dark (1941)? Allegro (1947) and Gypsy (1959)? 1776 (1969) and The Threepenny Opera (1954)? Fiddler on the Roof (1964) and A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum (1962)? Maytime (1917) and Sometime (1918) and Jim Jam Jems (1920)?

Company, furthermore, has a narrative design that is heavily influenced by revue. Earlier offerings of the sort include Bye Bye Birdie (1960), Count Me In (1942), and Oh What a Lovely War (1964), an episodic commentary on the subject of war that blends documentary and commedia dell’arte. Love Life (1948), in particular, masquerades as vaudeville by way of revue. The Apple Tree (1966) consists of three vaudeville tabs. And Little Me (1962) is a show-business sketchbook, perhaps best described as a cinematic vaudeville or a cinematic revue. It involves a tight-knit collection of blackouts, crossovers, interludes, and full scenes, most of which have been accented with stings, underscores, fanfares, and tags. The chronological plot, which traces the eventful rise of a busty young woman from the wrong side of the tracks, is played primarily through episodes involving a “Young Belle,” while an “Older Belle” effectively serves as the show’s narrator, courtesy of a framing device that finds the brassy dame revealing her life story to the author of her forthcoming memoir. And an added conceit positions the piece as a star turn for a male comic – originally Sid Caesar – who plays seven of the men in Belle’s life: two are father and son, and the other five die. Is this the expected structure or classical musical theatre form of which you write?

“A Chorus Line solidified the idea of the ‘concept musical’ – in which a central idea, theme, or theatrical conceit dictates form”

A Chorus Line (1975) is a brilliantly structured and extraordinarily effective musical, but how does it solidify the idea of the so-called “concept musical” – which, to be clear, is a meaningless term commonly used to denote musicals that traffic in nontraditional storytelling, typically characterized by some combination of a thematic and or a psychological narrative, absent a purely linear plot; a framing device; an abstract environment; theatrical comment; and episodic construction, after the fashion of original revue.

Earlier works that traffic in nontraditional storytelling include Allegro (1947), Cabaret (1966), Company (1970), Knickerbocker Holiday (1938), Lady in the Dark (1941), Love Life (1948), Man of La Mancha (1965), Oh What a Lovely War (1964), Peggy-Ann (1926), Reuben, Reuben (1955), Stop the World – I Want to Get Off (1962), and one might make an argument for Little Me (1962).

Three of the earliest works of the sort are As You Were (1920), The Comic Supplement (1925), and Noah’s Ark (1907), which unfolded in two acts set in two different time periods with a related cast of characters. The first act took place atop Mount Ararat-on-the-Bluff, just after the flood, and it centered around Noah’s handy man, Bill. The second found Bill & Co. reincarnated four thousand years later, in similar personages, working at an amusement park, known as “Paradise,” on the Island of Santa Catalina off the California coast. (Noah runs a merry-go-round.) But, the “old friends” do not recognize each other, or “their former relation,” until what the musical’s author, Clare Kummer, describes in the script as a “psychological moment.”

The popular labeling of shows as either “concept musical” or “integrated musical” is an arbitrary and purposeless practice, and it is wreaking havoc on the art form, for a musical is a musical is a musical is a musical. All of the elements need be integrated, or seamlessly woven together in the service of a single, theatrical statement, a unified, theatrical whole, if the piece is to be complete and dramatically effective, regardless of whether or not it is telling a traditional story, and each individual song need not necessarily extend dialogue or propel plot.

“In this production, the orchestra sits centerstage, immediately signaling that this is something different”

Different than what? Dead Outlaw, a brilliantly written musical currently running on Broadway, has a band that sits centerstage. Passing Strange (2007) had a band that sat centerstage. I Love My Wife (1977) had a band that sat centerstage and took part in the action. The Last Sweet Days of Isaac (1970) had a band that sat on an elevated platform and commented on the action. And The Band’s Visit (2016) and No Strings (1962) wove some of its musicians into the staging.

“The conceit of a recording session in a studio centers the play in the concept musical tradition, where the making of the recording becomes the central dramatic event of the piece”

The recording session, in Buena Vista Social Club, is not a conceit. Juan de Marcos wants to make an album, and, having already hired the musicians, he must get Omara Portuondo to be his lead vocalist. Over the course of the show, he visits her home to entice her, she visits the studio with skepticism, he auditions his arrangements for her, she warms to the idea of making the album and agrees to sing a song, she leaves the studio after an emotional and psychological incident during the recording of said song, he visits her home to get her back, a musician visits her home to get her back, she visits the ruins of the old club and is met by the ghost of her sister, she visits an old flame, and she returns to the studio, with her old flame, ready to record. That is a plot, and the recording session, as Marco Ramirez has written the musical, is a plot element, not an overarching conceit. Plus, Buena Vista Social Club does not have a definite dramatic center, in part because the 1996 plot has been neither fleshed out, nor consistently charged, nor effectively balanced and intertwined with the 1956 plot. And, by the way, the overall narrative design is not new. Bright Star (2016), for instance, has two interconnected linear plots that unfold simultaneously in two different time periods.

“The form of Buena Vista Social Club stands as a bold act of defiance against the sanitized, the predictable, and the conventional”

I do not know what you are intending to convey with the terms “sanitized” and “conventional,” which I do not personally use to mean “traditional,” but Buena Vista Social Club is not defiant in form (i.e. shape). It has a standard dual-world design with linear plots, performance pieces, and (sporadic) narration. Several musicals, like City of Angels (1989), have a personalized variation on the same. If you are referring to, as the specific act of defiance, the decision to retain and perform the Spanish-language lyrics, that is a matter of content, not form.

“This show’s decision to not translate the lyrics declares a seismic departure from the classical musical theatre form, where the most commonly preached dictate of theatrical songwriting is that songs must propel the plot”

There is no such thing as “the classical musical theatre form.” And there has never existed a rule that songs written for a stage musical must propel the plot. Even Oscar Hammerstein II was using performance pieces, like “Bill” and “Can’t Help Lovin’ That Man” from Show Boat (1927) and “Let Me Give All My Love to Thee” and “The One Girl” from Rainbow (1928), to serve a dramatic double purpose, propelling the story. (Propelling the plot is quite different than propelling the story and deepening character.)

“The songs do indeed continue the narrative of the play, just not in the way we’re used to”

I cannot – nor can you – say just what the collective “we” are used to, but the broader implication does not hold water. Jersey Boys (2005), for instance, employs most of its preexisting songs in the same manner that Buena Vista Social Club does, and Pal Joey (1940) is one of many, many musicals that employs some or all of its original songs as performance pieces.

“It is, in fact, a brilliant and essential act of authenticity”

Your points with regard to the reasoning behind the retention of the original Spanish-language lyrics are important, and, strictly from a standpoint of lyric and music performance, Buena Vista Social Club is absolutely “a master class in authenticity.” So, why is that not enough? Why have you sailed well beyond those important lyrical points, and attempted, without facts or foundation, to position the musical as a ‘revolution’ in form, misrepresenting the art form in the process?

Unfortunately, your misrepresentations are symptomatic of a wider problem that finds many or most of today’s artists and cultural critics rushing, blindly, to brand the latest offering as new and different and breaking the form. But there is no one way to make a musical, and there are, at this point, few things, in principal, that have not been seen on the musical stage. Even Afro-Cuban music, authentically performed, would not appear to be entirely new, for the late 1930s saw a number of Spanish-themed nightclubs on Broadway, with Cuban pianist and composer Eliseo Grenet, for instance, leading an eleven-piece band at Club Yumuri, and Cuban entertainer and stage director Sergio Orta producing several of the floor shows at Havana Madrid. “All the music I have used is authentically Cuban,” he explained. “Before I came to this country, I collected 500 pieces of music, including Afro-Cuban songs, Cuban folk songs, rumbas, comparsas, sons, nanygo rhythms, and guarachas.” (I cannot speak to whether or not the lyrics were performed in Spanish.) To quote a couplet from Sunday in the Park with George (1984), “Let it come from you, then it will be new.” And perhaps what said artists and cultural critics mean to say is breaking their own (mis)perception of the form – specifically the art form.

We must, to that end, be more specific and measured in our theatrical discussions – which does not mean we should lack passion and enthusiasm – and we must be better informed. The popular inclination to dismiss or lump together every musical that was written prior to the 1970s because of what one (incorrectly) perceives as having been, prior to the 1970s, a single story, a single sound, a single style, or a single, expected, classical structure is putting contemporary and future artists and shows at a serious disadvantage, for one is, in effect, dismissing the established art of musical storytelling – the craft, the methods, the mechanics – that was consciously and deliberately developed, bettered, and matured during that same time, irrespective of the subject, themes, and traditional or nontraditional nature of the story. And one is, in effect, severely limiting their theatrical frame of reference, their ability to speak meaningfully and seriously about the art form, and, perhaps most importantly, their artistic toolkit.

Respectfully,

Ben West

Correction: An earlier version of this article listed The New Moon (1928) instead of The Desert Song (1926). Both were written by Oscar Hammerstein II, but the latter was a collaboration with Otto Harbach.

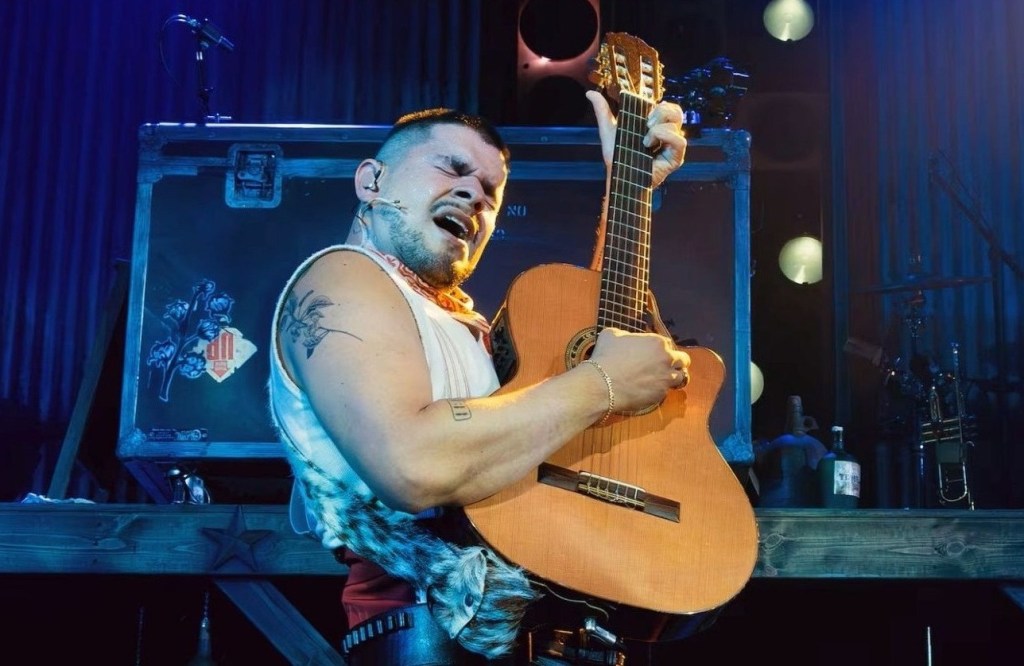

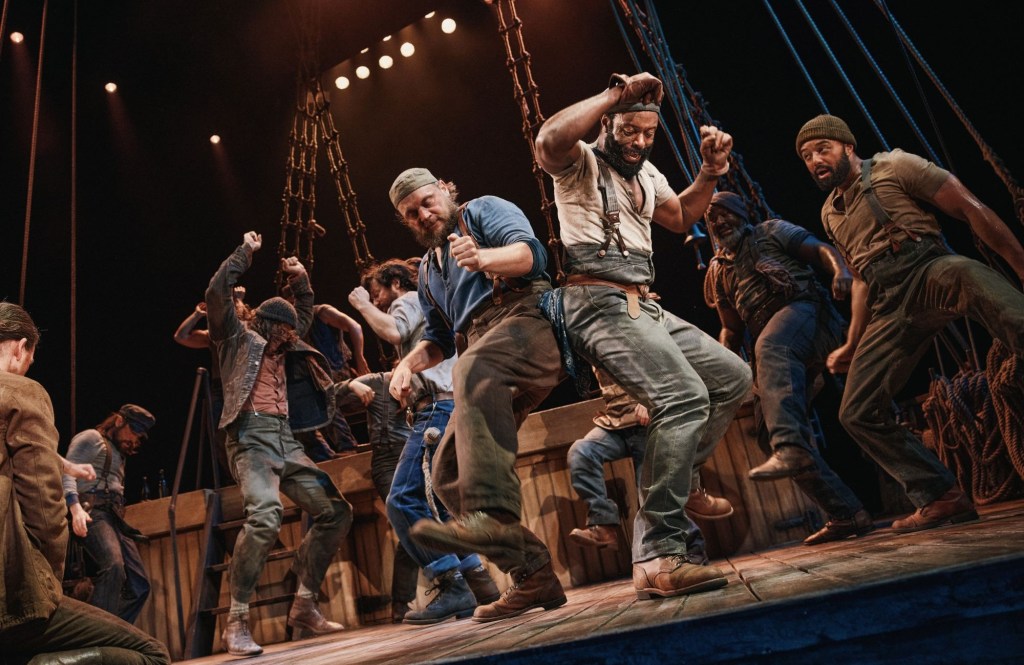

Photo of a scene from Buena Vista Social Club by Matthew Murphy.

3 responses

-

It’s so frustrating when people who should know better cart out hyperbolic statements like this. As much as I love Oklahoma!, Company and A Chorus Line (especially those last two,) they almost seem like arbitrary choices, but ones I wouldn’t expect Buena Vista Social Club, for all its great points, to be listed among in the future.)

However, since you’re nitpicking, I’m gonna nitpick back and point out that The New Moon had Hammerstein lyrics with no Otto Harback involvement. I love seeing Harbach get his due, but I think you were thinking of The Desert Song (which is in many ways a very similar show of course.)

-

Indeed! Thank you for that. I will swap out those titles accordingly. Appreciate the correction.

LikeLike

-

Leave a comment