A journal for industry and audiences covering the past, present, and future of the musical stage.

Chess, a new adaptation of the 1988 musical, opens tonight on Broadway at the Imperial Theatre. It has a book by Danny Strong, lyrics and original concept by Tim Rice, music by Benny Andersson and Björn Ulvaeus, and direction by Michael Mayer, and it is a numbing theatrical travesty.

The musical unfolds in two disconnected acts, set successively in 1979 and 1983, and powered respectively by the signing of SALT II, an arms treaty between the United States and the Soviet Union, and the commencement of Able Archer, a nonconfrontational military exercise conducted by NATO. Freddie Trumper is an arrogant American chess player who comes from a broken home. Florence Vassy is his Hungarian-born lover and advisor of seven years. Anatoly Sergievsky is a Soviet-Russian chess player with a wife, Svetlana, and children. Alexander Molokov is his advisor, and a member of the KGB. And Walter de Courcey is an FBI agent, described as a dick.

The plot, in the first act, involves a political scheme between Molokov and de Courcey, an affair between Florence and Anatoly, a threat of deportation, a bipolar disorder, a missing bottle of pills, a couple of press conferences, and a chess match between Freddie and Anatoly in which the former forfeits and after which the latter defects. The plot, in the second act, involves a new political scheme between Molokov and de Courcey, an encounter between Florence and Svetlana, an encounter between Anatoly and Svetlana, an encounter between Anatoly and Freddie, a private pep talk, a recorded plea, and a chess match between Anatoly and an inconsequential character in which Anatoly has a mental breakdown and after which he returns to Russia, without the threat of execution, given his recent win.

Strong and Mayer have endowed the piece with a severe and potentially striking presentational conceit, whereby the actor who plays the arbiter of the two chess matches also serves as the evening’s showrunner, introducing the characters, narrating the plot, commenting on the action, and relating the attendant themes to the global affairs of the present day. Plus, the ensemble is voyeuristic, with Greek chorus tendencies, and its members often sit on plush red couches that line the onstage perimeter of the playing space.

The sparse scenic design, by David Rockwell, consists of an elevated bridge mid-stage with a staircase left and right leading to the deck. The orchestra, led by Ian Weinberger, ornaments the staircases and the bridge; the upstage cyc holds light, video, and projections; the leg of each wing features shelves of super-sized chess pieces; miniature moving-head stage lights dot the interior of the proscenium; and a small vertical video screen occasionally descends center stage, directly in front of the bridge.

Chess commences with an overture, performed without passion, which is particularly problematic considering the corresponding melodies are often comprised of repeated notes and phrases, but the top of the show is otherwise intriguing and intermittently promising, even, from time to time, exciting. The showrunner takes the stage and sets the political scene, leading a thumping rendition of “Difficult and Dangerous Times,” supported by the ensemble, outfitted, by Tom Broecker, in gorgeous sleek gray suits. The fine choreography, by Lorin Latarro, is comprised of sharp, angular movements, complemented with precisely timed orchestral hits, and the entire sequence goes a long way toward establishing the highly stylized world of the show.

Thereafter, the showrunner sets the musical scene, and though the second scene-setting registers as something of a structural blunder, the blunder is momentarily forgiven. Anatoly and Molokov make their first entrance, the ensemble applauds, and a short scene of dialogue leads, acceptably, if unremarkably, to “Where I Want to Be,” an interior interrogation for Anatoly, who is backed by the hyper-mannered ensemble, and a projected snowstorm. And the surprisingly taught staging of the feverish, musically menacing solo, adorned with thunderous chorus vocals, winds up successfully distracting from the empty, unspecific, nondramatic lyric, while shrewdly complementing the final line – and reinforcing the essence – of the same, with Anatoly physically ending the song in the same stage-left position he began it. (“Where will I be? Back where I started.”)

Then, Freddie and Florence make their first entrance, the ensemble applauds, and the musical spins passably onward, accumulating additional blunders along the way, until the delicious transformation, roughly a third of the way through the first act, of the showrunner into the Arbiter, courtesy of “The Arbiter,” which is almost certainly the most electric, exciting number in the show, though it contains a purposeless, dramatically unproductive dance break in which the previously sharp, angular choreography loses a distinct identity and a particular point of view, and in which the Arbiter does not participate. (The break is, in principal, earned, but, in execution, faulty.) And the remainder of the musical runs down hill.

Chess is often said to have a great score, but it unequivocally does not – if, by great, one means well crafted, distinctive, and dramatically effective. The songs, especially in terms of the music, which has a certain vitality, may be wonderfully invigorating and hugely profitable in the popular-music sphere, for concert, radio, and recording, and I will freely admit to enjoying many of the songs from Chess under such inherently different circumstances, but the songs, even the introspective soliloquies, wilt on the theatrical stage, largely failing to serve the story, situations, and characters for which they have been written. Examine the lyrics. Examine the relationship between the lyrics and the music. Examine the music, in context. And examine the dramatic function – and effectiveness – of each song, in deepening, furthering, and propelling the narrative.

The original book, by Tim Rice, and the subsequent book, by Richard Nelson, are not solely to blame for the musical’s dramatic failures, and neither is the new book – though, in this case, the book writer chose to resurrect the infirm property of his own accord, and he has simultaneously failed to find a way to consistently and effectively theatricalize its patently untheatrical score, often placing the independently popular pop songs in the minds and mouths of murky characters, devoid of personality and clear, continuous motivation, sabotaged by surface-skimming dialogue and a convoluted plot, mechanically rendered; and often providing the murky characters with no reason to sing, and the musical with no dramatic foundation for song – especially in the outright embarrassing second act.

“Heaven Help My Heart,” “Nobody’s Side,” and “Someone Else’s Story” are horrific solos, for Florence, that lay down and die on the stage of the Imperial Theatre – though the first-named gets a mildly theatrical elevator entrance dead center. “One Night in Bangkok” is a lethargic act-two opener that finds Freddie getting dressed and doing drugs, with the assistance of a half-naked ensemble. “Pity the Child” is a painfully extraneous power-ballad, for Freddie, that actor Aaron Tveit, on the evening of November 11, could not even sing. “Anthem” is a babbling first-act finale, with protracted sentences and nonsensical poetic verbiage, that finds the sound design, by John Shivers, and the proscenium’s miniature moving-head stage lights doing much of the work. (Kevin Adams designed the solid lighting.) And “I Know Him So Well” is an excruciatingly dull eleven o’clock duet, for Florence and Svetlana, that has been given a regulation staging, with the two women eventually walking toward each other, meeting center, and stepping down front. The song, by the way, follows their flimsy, laughable encounter on the bridge.

“Quartet (A Model of Decorum and Tranquility)” does not effectively build to the point at which it must be broken off by dialogue. “Mountain Duet” does not effectively transition, lyrically or musically, from two concurrent inner monologues to an active conversation between Anatoly and Florence. And “The Deal” is a massive second-act sequence that drones on for what feels like days, with no evident escalatory support from the music arrangements or orchestrations, and with a ridiculously rough segue to a short reprise of the chorus of “Nobody’s Side” for the finish, accompanied by the pretentious vocalizing of actor Lea Michele, as the terminally elusive leading lady. (Brian Usifer, late of Swept Away, is the musical’s unsatisfactory music supervisor.)

“He is a Man, He is a Child,” meanwhile, might be a fabulous cabaret number, and Hannah Cruz, as Svetlana, might have knocked it out of the park, but the number has little to do with the sudden threat to Svetlana’s life by the KGB that immediately precedes it, or with the urgent decision that she must now make whether or not to help the agency. If Strong had slotted the standalone solo immediately after her introduction by the showrunner, and immediately prior to her scene with Molokov, Strong and the musical might have been in some sort of business, especially with Svetlana’s dynamic elevator entrance, somewhat diminished by the mechanism’s use in the first act. (Svetlana is introduced at the top of the second.) But Strong has not slotted the song as such, and Cruz is left to try building a tour de force on soggy ground.

Indeed, Chess is dramatic swampland. The principal characters are secondary, and the secondary characters are principal. The relationships are nonexistent, and so is the danger of nuclear annihilation. The first-act chess match, accented with the inner thoughts of Freddie and Anatoly, is poorly executed. The underscoring of certain scenes between Molokov and de Courcey is static. Anatoly’s eleventh-hour breakdown, during the second chess match, is seemingly endless, and his win is a nonevent. Strong has wasted the potentially seismic impact of his female star’s first sung vocal by burying it in a press conference. And the surprise entrance of Florence’s long-lost father moments before the final curtain is asinine. (“Oh, Papa!”)

Plus, the showrunner is underdone. A number of comments that he makes about the “cold war musical” register as derisively kitschy and call into question his – and the book writer’s – point of view. His retorts after “He is a Man, He is a Child” and “One Night in Bangkok” are cheap and deflating. His finger-snapping, as a means of controlling the world, is inconsistent. And Strong regularly has him telling the audience what has just happened onstage, or what is about to. Nonetheless, the showrunner is an incredibly fine idea, and might have proven profitable in more skilled hands.

Incidentally, Mayer is a terribly skilled director, but he seems to be losing his touch, or his taste. Still, he has retained a modest grip on the stage of the Imperial, and he has devised, for his staging of Chess, a number of shrewd tactics, like the showrunner serving as the keeper of the pills, and the regular, unostentatious placement of Freddie in a spotlight, echoing the metaphoric spotlight of which Freddie sings. But the activation of the ensemble is somewhat inconsistent, due in part to the material. The projections, by Peter Nigrini, are occasionally suspect. And the performances that Mayer has elicited are mostly poor – including those of Michele and Tveit.

Nicholas Christopher, as Anatoly, is no better than his fellow headliners, and fiddling in one’s hand with a white chess piece from time to time is not the same as carving out a complete, idiosyncratic character. Bradley Dean, as Molokov, is unremarkable, and Sean Allan Krill, as de Courcey, is moderately engaging, blessed with some of the show’s more playful, individualized dialogue. But Bryce Pinkham, as the Arbiter, is outstanding, in spite of the material deficiencies with which the entire cast is faced. And Cruz is incredibly strong.

Chess is a horribly written piece of theatre, and the fact that it continues to be performed – and embraced – speaks directly to the unfortunate state of the musical stage, much like the cold war musical, decades in the making.

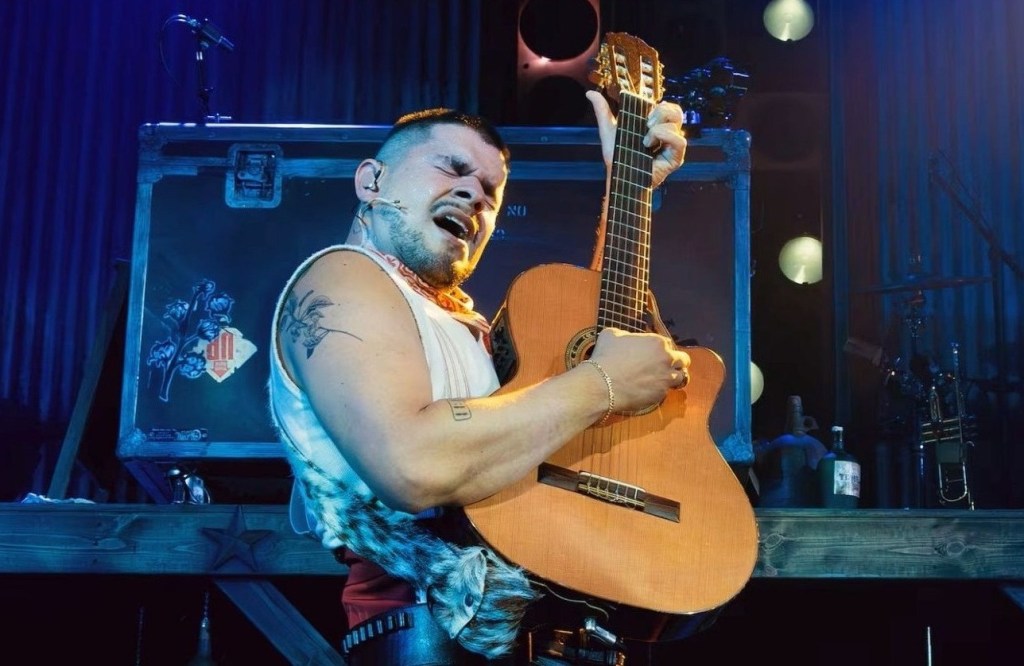

Photo of Aaron Tveit in the 2025 revival of Chess by Matthew Murphy.

2 responses

-

I haven’t seen this production, but this observation of yours gave me the shivers: “Strong regularly has him (the showrunner) telling the audience what has just happened onstage, or what is about to.” 😬

LikeLike

-

I saw a version a couple of years ago at the Muny with Jessica Vosk, which I think was somewhat better. I thought the fate of Florence’s father was left ambiguous, at least in that version.

LikeLike

Leave a reply to richlecomte48410b892a Cancel reply