A journal for industry and audiences covering the past, present, and future of the musical stage.

Dead Outlaw, a new musical tracing the life and death of Elmer McCurdy, opened on April 27 on Broadway at the Longacre Theatre. It has a book by Itamar Moses, lyrics and music by Erik Della Penna and David Yazbek, and direction by David Cromer, and it is now, following a number of small, impactful refinements that have been made to the material, the composition, and the staging since the musical’s mixed-bag Off-Broadway premiere, a top-drawer production of a brilliantly written and conceived piece of theatre. (Yazbek is credited with the concept.)

McCurdy, a real-life outlaw, was born in Washington, Maine in 1880 and killed by a sheriff’s posse in Osage Hills, Oklahoma in 1911. His life involved a drinking habit, a fighting habit, a stint in jail, a stint in the army, a failed romance, and a handful of attempted robberies, principally in Kansas and Oklahoma. His death, meanwhile, involved motion pictures, side shows, and a cross-country footrace, for his body was not buried until the late 1970s, when it was discovered hanging in a California amusement park.

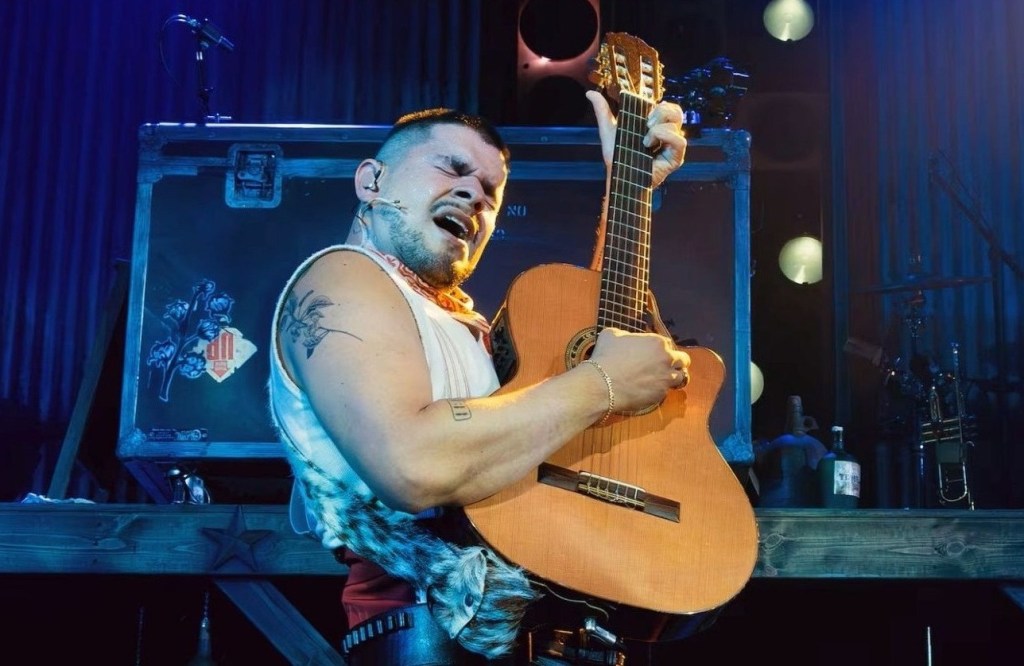

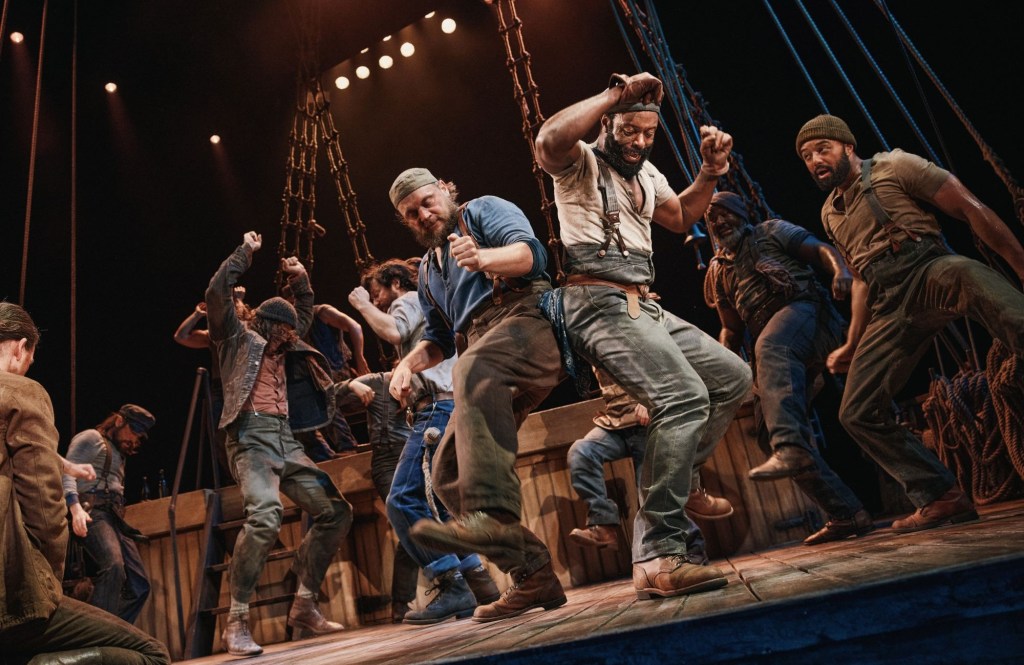

The musical, running 100 minutes, presents McCurdy’s unbelievable true story as a tragicomic American folktale, with a nitty-gritty five-piece band holding court center stage on a rustic, barroom-esque unit, flavored with Americana. Jeb Brown leads the cast of eight as Bandleader (i.e. Storyteller), narrating the story and briefly doubling as Jarrett, the leader of a gang of bank robbers. Andrew Durand plays McCurdy. And the six other actors genuinely and thoroughly transform into numerous other characters, with no trunk in sight.

Dead Outlaw is a blazingly theatrical affair with a distinct, individual world and a distinct, individual manner, and it has been crafted with tremendous skill. The storytelling is pristine, the integration of elements is seamless, and the narrative freshness fails to cease, helped along by the decision to pattern the plot in an ingeniously intricate fashion and to outfit the musical with a dynamic composition.

Yazbek & Co. have, to that end, realized an expert balance and blending of narration and dramatic action, of dialogue, underscoring, musical sequences, and song, and they have shrewdly intermingled, in spinning their tale, multiple time periods, beginning the show with a prologue that, beyond establishing the language of the storytelling, reveals a glimpse of the soon-to-be-dead outlaw in 1911, and separately introduces the discovery of his hanging body in the 1970s. Thereafter, the musical jumps back in time to the beginning of McCurdy’s journey and moves, in essence, chronologically, referencing, briefly, the show’s two opening moments when each comes up again in the chronological timeline, but it wisely keeps the 1970s in play, as well, courtesy of three well-timed trips, spread over the course of the show, to a coroner’s office, with the final trip marking the point at which all of the action has been brought up-to-date, and culminating in song. The two prior trips were strictly spoken.

Every moment – or nearly every moment – in Dead Outlaw is unpredictably rendered, with a sense of detail, distinction, and inevitability, and the result is a meticulously calibrated, seemingly spontaneous affair that stays on top of its storytelling and on top of its audience, getting neither ahead nor behind, and constantly surprising. The onstage death of the central figure, for instance, is devoid of gunfire, despite involving roughly a half-dozen guns, and a late-show interlude concerning that cross-country footrace is narrated by a different actor, Trent Saunders, after the Bandleader turns over, for the first and only time, his microphone. Even the musical’s use of threes, including the three trips to the coroner, puts a personalized, story-driven, and, thus, surprising spin on the age-old theatrical device.

Three back-to-back television reports, delivered in the prologue, are sharply overlapped, with the first two lines getting cut off before completion. Two back-to-back instances of McCurdy, in Maine, getting drunk and storming stage left to attack a man are followed, roughly 10 minutes later, by an instance of McCurdy, in Kansas, getting drunk and storming stage left to attack a man – except a song, “Killed a Man in Maine,” takes the place of the third attack. And two botched bank robberies, presented back-to-back within the frame of a song, “Blowin’ It Up,” are immediately followed by a botched train robbery, presented within the frame of a separate song, “Indian Train.” (The entire robbery sequence has been significantly tightened since the show’s downtown run, though the new musical staging, by Ani Taj, for the former number is a trifle untidy and nondefinitive.)

Dead Outlaw similarly employs, to great effect, parallelisms, like McCurdy beginning the show and ending his life on a platform atop the band unit, singing a ballad and reaching for the stars; juxtaposition, coupled with sharp tonal shifts, like the two songs that comprise the prologue; and reprises, like McCurdy, dead, reanimating for a moment to sing a few lines of “Nobody Knows Your Name” before his mouth is sewn shut, or a small delegation from Oklahoma, late in the show, singing a few lines of “Our Dear Brother” when they attempt to claim McCurdy’s body from the coroner – an echo, laced with sinister humor and serving as a valuable misdirect, of an earlier scene when two men attempt to claim McCurdy’s body from a different coroner. The first instance of the classy, unhinged serenade employs a stop-time whistle chorus, perfectly synchronized with the counting of dollar bills for a bribe.

The comedy in Dead Outlaw is sharp, witty, deadly serious, and seriously earned, rooted, at all times, in situation and character, and the dialogue is the stuff of genius: organic, flavorful, individualized, and astoundingly efficient at establishing, in a dramatically active manner, character, relationship, and setting. Look no further for evidence than a scene, early in the show, that finds McCurdy happening into a store after having just arrived in Iola, Kansas. And revel in the musical’s first line: a short, inviting first-person declaration, composed of roughly a dozen words and spoken in the clear, that instantly grounds the title, subject, and narrative style, while simultaneously cultivating a personal connection between Bandleader and audience. Plus, Moses has mined, through judicious interjections, presumably all of the gold to be found in the fact that this insane tale is true.

Each of the characters feels full, even those that deliver little more than a single line, and the use of doubling feels deliberate and considered. Note, for instance, the three hapless characters successively essayed by Dashiell Eaves. The use of “Part One” and “Part Two,” as spoken by the Bandleader, certainly makes sense, given the life-and-death nature of the narrative, but it seemed mighty dangerous downtown, likely owing to the lax staging and the occasionally unfinished material. It nonetheless works perfectly well uptown, under the refined and considerably tighter circumstances, and the movement into “Part Two” is delicious. Similarly insignificant uptown is the question, from time to time, of timeline.

The score is outstanding: vital, distinctive, and oozing character. Yazbek has demonstrated, throughout his stage career, a real understanding of theatricality and musical storytelling, and it is palpably present here. (Dead Outlaw is my first encounter with his fellow songwriter.) The neatly balanced routine is composed of multiple musical styles, each of which has been tailored to the needs and emotional pitch of the respective moment, and all of which have contributed to the creation of an individual and cohesive sonic tapestry. The melodic lines are notably expressive, built with an extraordinary sense of movement, of drama, and of narrative propulsion, often steadily climbing up or down the staff, sometimes with modulated phrases, and occasionally playing with extremes, juxtaposition, and the like. The lyrics are smart, playful, peppered with idiosyncrasies, and almost always active, despite veering, every now and then, toward the poetic and harboring, here and there, an unsteady scan or a false rhyme. Plus, the “Opening” offers a beautiful example of how to craft deliberately free lines!

“Killed a Man in Maine,” in particular, is a four-alarm firecracker, consisting primarily of rapid-fire, unpitched patter, deliriously violent, and it is now, given the addition of a button, complete, and completely exhilarating. The initial iteration of the song, as seen downtown, had no button or definitive ending, which deflated the moment and the momentum, and caused a small narrative schism. “Normal,” meanwhile, is a gorgeous mid-tempo number with a warm melodic line, coupled with warm vocal harmonies, situated on top of a gently rustling drum figure, and it has been significantly boosted by a reassignment of lyrics. The song is now begun by the Bandleader, who hands it over to McCurdy, who hands it over to his love interest, Maggie, and it is a sensational bit of storytelling.

“Nobody Knows Your Name,” sung by McCurdy, is a dynamite number, complemented with sharp, minimalistic choreographic movements executed by McCurdy atop the band unit. “Millicent’s Song,” sung by a lonely young woman to a corpse, is a fabulous three-part time-lapse sequence with a disarming intimacy and vulnerability – which are nearly stifled by two hastily assembled transitional tableaux, added since the downtown run. (The tableaux are clever, countering the tender lyric with mad humor, but they might be more smoothly executed.) “Andy Payne” is a rocking solo, with a soaring melodic line, but it suffers from a mediocre performance, by Saunders, and momentarily unsteady direction that finds Saunders narrating the story and acting it out at the same time. (“Andy Payne” was, at one time, extraneous, carrying no connection to McCurdy and culminating with a Billy Graham parable, but the authors have skillfully pulled the ace number back from the brink.) And “A Stranger,” sung by Maggie, is a beautiful standalone, but the lyric is still not especially theatrical. The song has, however, been given, courtesy of the staging, a dramatic lift; Maggie’s move to the band mic is now clearly motivated; and the number successfully lands.

The theme song, “Dead,” is a rip-roaring item, with a catchy chorus built around a list of names. But the list has little sense of escalation or topping, despite transitioning, over the course of the show, from the names of the deceased to the names of the living. (Zendaya was mentioned during a reprise on the afternoon of April 26.) Still, the song works. It might simply have worked better with a more deliberate or increasingly irreverent progression of names. And one still wishes for a more definitive lyric in “Crimson Thread,” which closes the show and continues Yazbek’s fascination with umbilical cords. (See “Madrid” from Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown.) A bit of closing dialogue intertwined with “Crimson Thread” is nonetheless deeply affecting.

The orchestrations, by the two songwriters and music supervisor Dean Sharenow, late of Buena Vista Social Club, feature banjo, mandolin, and lap steel, acoustic, and electric guitar, and they are exemplary. They speak to story, character, and lyric, and they are instrumental in distinguishing the world of the show. The vocal arrangements are incredibly fine. Rebekah Bruce leads the crack band, and JR Atkins replaces Della Penna, who played the show downtown. Atkins is significantly stronger than Della Penna in his delivery of the solo vocals on “Crimson Thread” and “Dead,” and the production greatly benefits.

Cromer has given the piece an incredible staging that feels integral to the narrative composition, and serves, at all times, the story. It is sharp, inventive, and visually striking, with an invaluable assist from lighting designer Heather Gilbert. It makes good use of the stage, and nearly every moment feels definitive, purposeful, and dramatically earned. An early dialogue sequence concerning McCurdy’s childhood initiates the production’s use of light, dark, isolation, and shadow, with strategically placed slats of downlight on either side of the band unit, and it is fantastic. (The lighting of this scene has been finessed for the Broadway run.) A pin-spot moment, late in the show, is out of this world. The three trips to the coroner unfold on alternate sides of the stage. The first move of the mobile band unit is caused by McCurdy, who pushes it, as a dramatic act, in the middle of “Killed a Man in Maine.” A coffin glides stage right before gliding stage left and directly into a tableau. And the coroner’s solo, “Up to the Stars,” is buttoned with a corded microphone ascending up to the stars in a pin-spot, such that a bank of television microphones may be placed below. (One of several buttons and transitions that have been profitably cleaned and tightened since the musical’s downtown run.)

Cromer, with Gilbert, has realized an electric onstage world, and the pair have maintained a physical freshness throughout. That said, a light snap delineating the exterior of a store could be more defined. The timing of a chandelier drop could be more deliberate. The blackout on the third reporter in the prologue should be much faster. And brief choreographic moments, presumably the work of Taj, in “Somethin’ ‘Bout a Mummy” and “Something from Nothing” should be sharper and more specific.

The character work, under Cromer’s direction, is, almost across the board, top-of-the-line thrilling. Brown, Durand, and Eaves, in particular, are excellent. Julia Knitel is excellent. Ken Marks is excellent. Thom Sesma is excellent. And each is giving a gloriously lived-in performance. Eddie Cooper is solid, and gives an excellent line reading as a train conductor. And Saunders is the only weak link in the cast.

The set, by Arnulfo Maldonado, is incredibly strong, and the versatile band unit never feels cumbersome. The costumes, by Sarah Laux, are incredibly fine, individualizing each of the characters, and the outfit for McCurdy is magic. And the sound, by Kai Harada, is clear and well balanced, and the atmospheric effects are well done. Unfortunately, Harada and Cromer have outfitted the actors with concert mic headgear.

Dead Outlaw is not flawless, but it is a brilliantly written work, and it moved me to tears, with its overwhelming artistry, on three separate occasions during a single sitting. Whether or not the story and the style will have mass appeal remains to be seen, but everyone who cares about the art of musical storytelling should experience and scrutinize this remarkable oddity, for it is, objectively, one of the best written new musicals of the 21st century.

Note: Related articles were published on June 9 under the title If Dead Outlaw Dies, Will Tony Culture Be to Blame? Plus a Reappraisal After a Second Visit; on June 23 under the title On the Closings of Dead Outlaw and Real Women Have Curves: Story vs Craft; and on August 26 under the title The Mishandling of Dead Outlaw Continues with a Cast Album Missing a Tambourine and More.

Photo of Andrew Durand and Jeb Brown in Dead Outlaw by Matthew Murphy.

Leave a comment