A journal for industry and audiences covering the past, present, and future of the musical stage.

Dead Outlaw opened on Broadway on April 27, and I immediately assessed the piece as being one of the best written new musicals of the 21st century. On Saturday, I paid the show a second visit, with my husband, who is not involved in theatre. Though I will refrain from restating the detailed analysis found in my earlier review, I feel compelled to reiterate how brilliantly this tragicomic American folktale has been written and how incredibly well it has been realized onstage. (See my review for analysis and background.)

Note, in addition to the numerous items already mentioned, the personalized language fashioned for each of the characters; the sharp buttoning of scenes and the deliberate building into song; the exquisite precision of the complex composition and intricate plot, including song entrances, scene shifts, and interplay between narration and dramatic action. Note the inventive overlap of the two coroners in the transition from “Part One” to “Part Two.” Note the balance, in the crackerjack musical routine, of whole songs and songs with interstitial dialogue, or sequences; and of songs with applause breaks and songs without applause breaks. Note the shrewd and charged return to dialogue following the songs with applause breaks. Note, beyond the nature of the melodic lines, the musical development, the escalatory shaping of the individual songs, often accomplished through the successive layering in of instruments, vocal harmonies, vocal interjections, and or additional motifs, like hand claps and stop-time. Note the ambient hum of the coroner’s office; the practical downlight used for the button of “Killed a Man in Maine”; the clockwise spiraling of the band unit, after the central figure nudges it counterclockwise, and the scorching red and gold hues that, at various points throughout the show, isolate and burn the same. This is the work of skilled craftsmen – smart and inspired craftsmen – with a shared vision, a singular point of view, and a serious understanding of theatricality. (Dead Outlaw has been written by Itamar Moses, Erik Della Penna, and David Yazbek, with direction by David Cromer.)

A separate word was said, in my review, for the stellar work of lighting designer Heather Gilbert, and a separate word must be said here for scenic designer Arnulfo Maldonado’s multifunctional mobile band unit. It contains two exterior ladders leading to an upper-level landing. It contains a practical metal rod upon which the central figure briefly hangs during his drunken tirade. It contains a series of wooden panels, two of which, on the downstage left edge, are backless, and briefly serve as the bars of a jail cell. It contains Christmas lights and practical lights and stage lights and a hidden backdoor, through which the character of Andy Payne presumably sneaks in order to make a surprise appearance, from behind a pull-down map, before his titular number. And the entire unit feels distinctive, and of a piece.

Six of the eight actors were excellent when I first encountered the production on the afternoon of April 26, and they have only gotten finer. Likewise the band, led by Rebekah Bruce under the supervision of Dean Sharenow. The sound, by Kai Harada, is pristine, and the sound effects are tasteful. And the musical’s few minor flaws remain, namely the performance and direction of “Andy Payne” and the choreography of “Somethin’ ‘Bout a Mummy” and “Something from Nothing.”

But Dead Outlaw is nonetheless a brilliantly written piece of theatre that has been given a top-drawer production, and the musical and the production should be experienced and scrutinized by everyone who cares about the art of musical storytelling. Even though the story – and perhaps the style – may not ultimately have mass appeal.

My husband, in particular, hated Dead Outlaw downtown, in its mixed-bag Off-Broadway premiere, and he liked it only marginally better on Broadway. (He refuses to see it a third time.) Though he laughed in places, liked the music, and loved the cast, especially Jeb Brown, Andrew Durand, and Julia Knitel, he loathed the story, and its lack of an overtly happy ending. (Which is certainly understandable, and does not negate the skill and ingenuity, the brilliance with which the musical has been made and the story told.)

Dead Outlaw has, however, a real catharsis, a hopeful release, marked by subtlety, in the closing narration, coupled with the attendant musicality, that involves the coroner’s instructions concerning the central figure’s burial. But the closing song, “Crimson Thread,” is surely a material weakness. Though the two songwriters have provided a brief, valuable narrative summation, they have done so in a strikingly obtuse and poetic manner, contrasting the interior and exterior of any and all human beings, by way of their central figure, using the impersonal pronoun “it’s” without a preceding proper noun (e.g. “Outside, it’s…inside, it’s…”). This brief passage ultimately registers as nondefinitive, and the impersonal pronoun creates an added challenge for an audience that has been trained, for decades, not to listen for the lyrics. The message is nonetheless there – for those listening. And, in any case, one wonders if the story is the largest factor in the musical’s apparent struggle to find a ticket-buying audience.

Dead Outlaw has been capitalized, according to a filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission, at $10 million. Its weekly grosses have been hovering around $500,000, which is notably less than its weekly operating costs, and the situation is simply not sustainable.

The musical’s Broadway transfer was formally announced on December 19, less than four months prior to the start of performances, with lead producers Lia Vollack and Sonia Friedman almost certainly rushing the show to the stage in order to be considered for – and seemingly with the expectation of winning some of – the recent season’s Tony Awards. (It opened on the cutoff date, and last night went home emptyhanded.) This decision was evidently made despite the months of March and April already being jam-packed with 17 high-profile openings, and rather than bringing the show to Broadway at a later date, albeit real-estate dependent, and in its own good time, with less immediate competition and with a fully considered marketing campaign that defines the musical, evokes its singular subject and character, and consists of more than old pull-quotes and old awards. (The show did not sell like gangbusters downtown, so I am unclear why the team felt that the title alone would sell the show on Broadway.)

If Dead Outlaw closes prematurely, the reasons will inevitably not be limited to one, and I do not mean to indict or chastise – nor is it my place to indict or chastise – Vollack and Friedman, who have championed an exceptional piece of theatre. But the situation in which they find themselves seems to speak directly to the commercial theatre industry’s all-consuming obsession with the Tony Awards, which is causing, to the detriment of audiences, artists, and shows, the entire Broadway season to be dominated by the same – especially preventing, to an extent, productions from standing and being taken on their own, and contributing to a regular spring rush.

I have already advocated for a return to the Tony Awards’ original design, with no formal nominees, no fixed categories, and no labeling of “the best,” and with a ceremony that might serve as a celebration of Broadway and a marketing tool for the industry and all of the season’s individual shows. But that is a matter for tomorrow. Today, Dead Outlaw is struggling.

Vollack & Co. have recently taken a new advertising tact, anchored by an exclamatory early line of dialogue and complemented with a dead-man-around-town social media gimmick. Let us hope one or both work, because Dead Outlaw is representative of the musical theatre at its creative best.

Note: A related article was published on June 23 under the title On the Closings of Dead Outlaw and Real Women Have Curves: Story vs Craft.

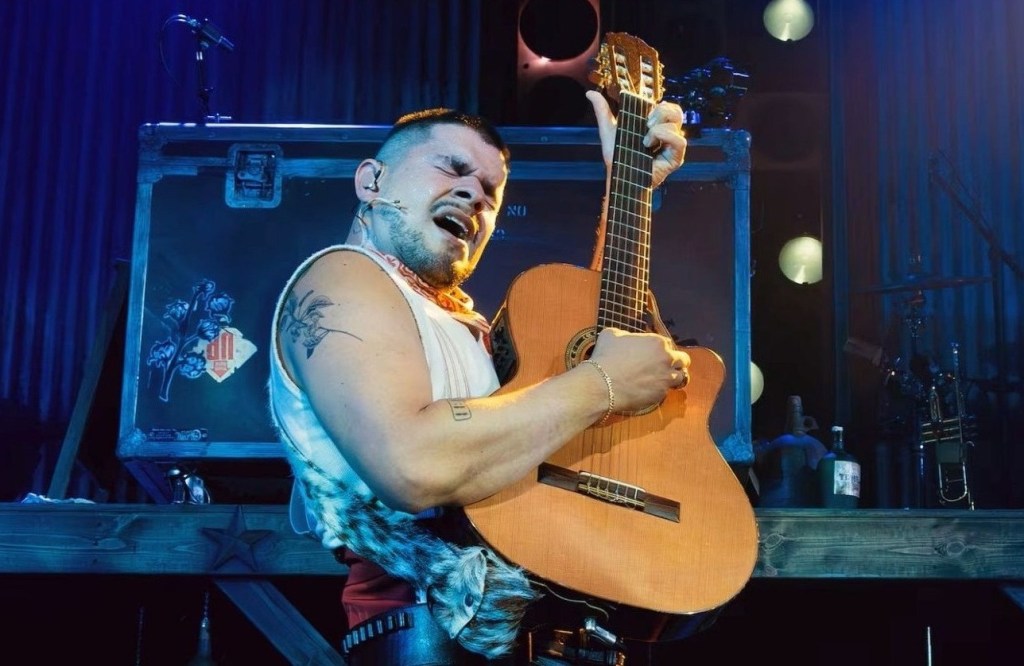

Photo of Thom Sesma in Dead Outlaw by Matthew Murphy.

Leave a comment