A journal for industry and audiences covering the past, present, and future of the musical stage.

The Jamie Lloyd production of Evita opened two weeks ago, and it is the latest offering to reaffirm the notion, asserted by an assortment of artists and cultural critics, that the musical theatre has entered a period of radical reorientation. Traditions are being shattered, forms are being broken, and the rulebook, for the first time since its creation in the last century, is being relegated to the bin. Thus, let us pay our respects to the official rules of musical theatre – which are finally being broken.

1. A musical must open with song, preceded by no more than a few lines of dialogue. Except Camelot (1960), Company (1970), Gypsy (1959), Lady in the Dark (1941), Man of La Mancha (1965), My Fair Lady (1956), Peggy-Ann (1926), and Skyscraper (1965) are among the musicals that do not open with song. Likewise original revues like The Little Show (1929).

2. All of the principal characters must be introduced in the first act. Except Melba Snyder is introduced in the second act of Pal Joey (1940), Marge MacDougall is introduced in the second act of Promises, Promises (1968), and the two ladies wind up stopping their respective shows.

3. Every musical must have a linear plot that unfolds in multiple locations over a relatively limited period of time. Except A Chorus Line (1975), 1776 (1969), and You’re a Good Man, Charlie Brown (1967) are among the musicals that do not strictly adhere to a linear plot. The linear plot of A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum (1962) unfolds entirely in one location. The linear plots of Gypsy (1959) and Show Boat (1927) unfold over a period of decades. The Apple Tree (1966) consists of three separate one-acts. And Call Me Mister (1946), Make Mine Manhattan (1948), and Stars and Gripes (1943), while technically original revues, are built around specific themes.

Plus, Chicago (1975) is played within the framework of vaudeville. City of Angels (1989) follows, simultaneously, the making of a private detective film in the 1940s and the plot of said film, complete with deliberate character doubling. How to Succeed in Business without Really Trying (1961) employs, as connective tissue, audio-rendered passages of the titular novel, currently being studied by the central figure. Jelly’s Last Jam (1992) traces the life story of jazz musician Jelly Roll Morton within an abstract purgatory known as the Jungle Inn, presided over by a Chimney Man. Knickerbocker Holiday (1938) dramatizes the 17th century events of a novel by Diedrich Knickerbocker with a framing device that finds Knickerbocker, in the 19th century, writing said novel and interacting with his characters. The Last Sweet Days of Isaac (1970) has an onstage rock band that sings songs commenting on the action. Little Me (1962) centers around a fictitious movie star, Belle Poitrine, with “Older Belle” revealing her life story to the author of her forthcoming memoir, “Young Belle” playing the chronological plot of said story, and a male comic playing seven of the men in her life. And The Threepenny Opera (1954) finds a Street Singer turning the crank on a sign box to reveal the written setup for each scene.

4. Every scene must be buttoned with a song. Except City of Angels (1989), Guys and Dolls (1950), and Of Thee I Sing (1931) are among the musicals that do not button every one of their scenes with a song. In fact, some of their scenes are completely songless.

5. Every song must advance the plot. Except a tremendous number of musicals contain introspective soliloquys, character songs, dramatic commentaries, thematic commentaries, celebratory production numbers, performance pieces, and the like.

6. The central figure or figures must have a major solo or lead a major musical number within the first 15 minutes of the show. Except Bye Bye Birdie (1960) does not give its leading man a song until a third of the way through the first act, and Oklahoma! (1943) does not give its leading lady a song until halfway through the same. Barefoot Boy with Cheek (1947), meanwhile, has a leading man who does not lead a musical number until the second act.

7. All of a musical’s emotional highpoints must be rendered in song. Except Assassins (1991), Gypsy (1959), The King and I (1951), and 1776 (1969) are among the musicals that contain explosive scene work, and the comedy in musicals like City of Angels (1989), A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum (1962) and Little Me (1962) is showstopping.

8. Encores are not dramatically effective, and they are forbidden. Except Hello, Dolly! (1964), Kiss Me, Kate (1948), and Sail Away (1961) are among the musicals that contain dramatically effective encores.

9. Spoken dialogue within a song must be initiated by a character who is not currently singing. Except Knickerbocker Holiday (1938), My Fair Lady (1956), and She Loves Me (1963) are among the musicals that have a song in which the character singing initiates the interstitial dialogue.

10. A musical must have an early song in which the central figure explicitly states what they want. Except Cabaret (1966) and The King and I (1951) are among the musicals that do not have such a song.

11. A musical must have a big finish. Except Cabaret (1966) and The King and I (1951) are among the musicals that do not have such a finish.

12. The first act of a musical must end with song. Except Fiddler on the Roof (1964) and A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum (1962) are among the musicals whose first act does not end with song.

13. The second act of a musical must begin with song, preferably a rousing up-tempo. Except Fiddler on the Roof (1964) and A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum (1962) are among the musicals whose second act does not begin with song.

14. A musical must have a showstopping number at the eleventh hour. Except Fiddler on the Roof (1964) and A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum (1962) are among the musicals that do not have such a number. And Gypsy (1959) has three.

15. The chorus of every song must adhere to the Broadway standard 32-bar AABA structure. Except Leonard Bernstein, Cy Coleman, Frank Loesser, and Harold Rome are among the composers whose work does not strictly adhere to the imagined Broadway standard.

16. A single character cannot sing two or more solos situated back-to-back in the routine. Except Gypsy (1959), New Girl in Town (1957), and Peter Pan (1954) have a single character who does.

17. A song cannot end with a single line of lyric repeated ad infinitum. Except “The Telephone Hour” from Bye Bye Birdie (1960), “Rose’s Turn” from Gypsy (1959), “Let the Sunshine In” from Hair (1968), and “Turkey Lurkey Time” from Promises, Promises (1968) do just that.

18. A single character cannot be played by more than one actor at a given time. Except Jelly’s Last Jam (1992) has two male actors playing the central figure and sharing the stage for a tap battle, and “Young Belle” and “Older Belle” share the stage for a late-show duet in Little Me (1962).

19. The principal characters in a musical must not die. Except Carousel (1945), Oklahoma! (1943), Rainbow (1928), and Sweeney Todd (1979) have a principal character who does.

20. A musical must have a central love story, and the central couple must share a romantic duet. Except Chicago (1975), City of Angels (1989), The King and I (1951), and 1776 (1969) are among the musicals that do not have a central love story, and the central couples in Carnival (1961) and Sweet Charity (1966) do not share a romantic duet.

21. A musical must have a title song. Except I Can Get It for You Wholesale (1962), A Little Night Music (1973), and Plain and Fancy (1955) are among the musicals that do not have such a song.

22. A musical must have an overture. Except A Chorus Line (1975) is among the musicals that do not, and Carnival (1961), Carousel (1945), and West Side Story (1957) begin with dramatic action in pantomime.

23. A reprise must contain a new or altered lyric. Except “Till There Was You” from The Music Man (1957), “New York, New York” from On the Town (1944), “Some Enchanted Evening” from South Pacific (1949), and “Ohio” from Wonderful Town (1953) are reprised with the original lyric.

24. Every principal character must have a song of some sort: solo, duet, etc. Except Professor Schultz does not sing in Barefoot Boy with Cheek (1947), Mrs. Peterson does not sing in Bye Bye Birdie (1960), Mayor Shinn does not sing in The Music Man (1957), and Ludlow Lowell does not sing in Pal Joey (1952).

25. A musical must have legs. Except Lost in the Stars (1949) and Regina (1949) do not have much in the way of legs.

26. A musical must have laughs. Except Lost in the Stars (1949) and Regina (1949) do not have much in the way of laughs.

27. A musical must have dancing. Except Lost in the Stars (1949) and Regina (1949) do not have much in the way of dancing.

28. A musical must not account for new technology. Except Bye Bye Birdie (1960), A Chorus Line (1975), Promises, Promises (1968), and Your Own Thing (1968) are among the musicals whose make-up has pioneered or capitalized on contemporaneous developments in lighting, sound, projections, motion pictures, machinery, and automation. Likewise original revues like The Band Wagon (1931), Flying Colors (1932), and Three’s a Crowd (1930).

29. A musical cannot have two different songs back-to-back in a single scene. Except Guys and Dolls (1950), Gypsy (1959), and South Pacific (1949) are among the musicals that do. Not to mention sung-thru musicals like March of the Falsettos (1981).

30. A musical must not intermingle actors and musicians. Except Cabaret (1966), Chicago (1975), I Love My Wife (1977), and The Last Sweet Days of Isaac (1970) are among the musicals that do. And the latter contains an element of concert.

31. A musical must not address social or political matters. Except The Cradle Will Rock (1937), Show Boat (1927), South Pacific (1949), and Your Own Thing (1968) are among the musicals that do.

There is, in fact, no one way to make a musical. No formula. No fixed pattern. No definitive book of rules. Furthermore, most of the items listed above concern the structure and composition of a particular property, and they are hardly the only items of the sort.

Take, for instance, the dream ballet, which has received comic and dramatic treatments in shows like Oklahoma! (1943), One Touch of Venus (1943), Pal Joey (1940), and Top Banana (1951). Take, as well, the post-lyric dance break, found in songs like “Put on a Happy Face” from Bye Bye Birdie (1960), “All I Need is the Girl” from Gypsy (1959), and “You Can Dance with Any Girl at All” from No, No, Nanette (1971). Take the add-on encore or the add-on reprise, employed in shows like Are You with It? (1945), with “When a Good Man Takes to Drink,” and A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum (1962), with “Everybody Ought to Have a Maid.” Take the split-stage scene, the split-stage song, the time-lapse, the freeze frame, the flashback, the aside, the blackout sketch, the interlude, and the crossover. Not one of these – and other – valuable narrative devices would be appropriate for the architecture of every musical, for every musical is inherently different, and necessarily has its own needs. Even musicals that happen to have been based on the same source material.

There is no one way to make a musical, but there remains an art to musical storytelling, a rigorous creative science, that was realized in the middle of the 20th century. This transformative period, during which the musical theatre matured, produced numerous stylistically diverse works of a seamless, unified, and expertly finished nature, and witnessed the development and refinement of a cornucopia of tools and techniques and methods and mechanics, coupled with refinements in craft.

Perpetuating the myth that there exist, stemming principally from this period of maturity, rules for the making of a musical, especially in terms of structure and composition, and fixating on the breakage of the same is doing no one any good. Our time should instead be spent taking a dive into the history of the art form, examining any number of works, especially from the middle of the 20th century and specifically from a practical perspective, and building, in the process, a wider frame of reference and a heftier toolbelt, such that the musicals of today and tomorrow, regardless of subject, theme, and musical language, might significantly increase their chances of realizing the possibilities, already proven, of professionalism and excellence in musical storytelling. And of being evaluated and recognized accordingly.

Most of the 70 musicals referenced above are well crafted and highly effective. Some are decidedly mixed. Many are exceptional. All are worthy of examination, for better or worse, and disregarding subject and theme. Several other quality musicals, from the 20th century, might have been referenced above, and they are similarly worthy of examination. There are creative riches to be mined in the past, separate and apart from revivals. And the 21st century has produced its own (small) collection of exemplary products, including The Band’s Visit (2016), Fun Home (2013), Hamilton (2015), and, most recently, Dead Outlaw (2025).

In the 1970s, the musical theatre entered a state of disarray, and, to an extent, it remains in such a state today, spurred on by a misunderstanding and dismissal of the musical theatre’s maturation, through a decades-long movement, begun about the 1910s and brought to a close in the 1960s, to better the art of musical storytelling, and by a revolt from nonexistent rules. But I believe that the future of the musical theatre remains bright, and I believe, perhaps foolishly, that every artist is capable of excellence. Even Bob Martin. Abandoning this false notion of rules will surely benefit everyone – though it must be acknowledged that the musical theatre nonetheless remains an incredibly challenging medium.

As for the Jamie Lloyd production of Evita, I have not yet seen it and cannot comment. But there is no rule that a musical must be presented entirely within a proscenium, and the Jamie Lloyd production of Sunset Boulevard was part of a larger and rather disturbing trend, perhaps not entirely new, that seems to find eventhood taking precedence over storytelling.

Note: A related story was published the following week under the title The Flip Side of Maturity, or What Made the Middle of the 20th Century Golden?

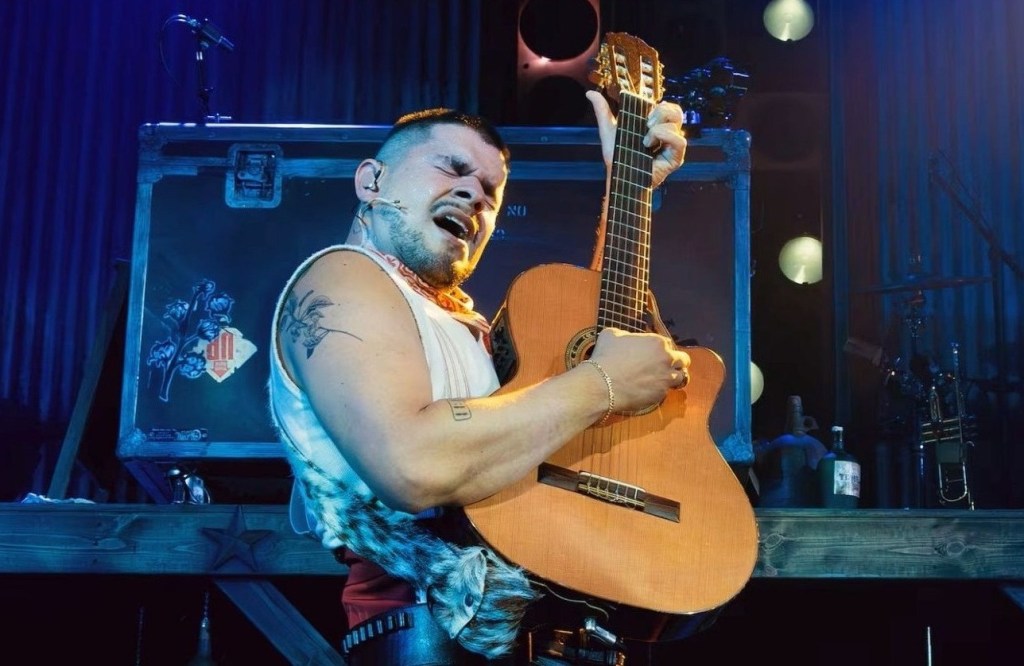

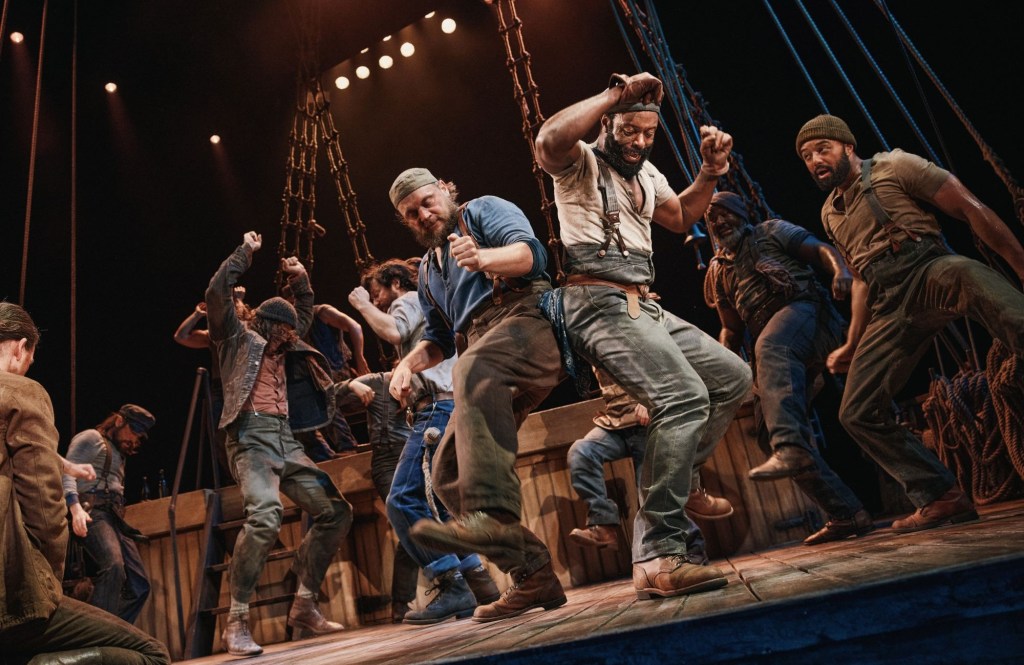

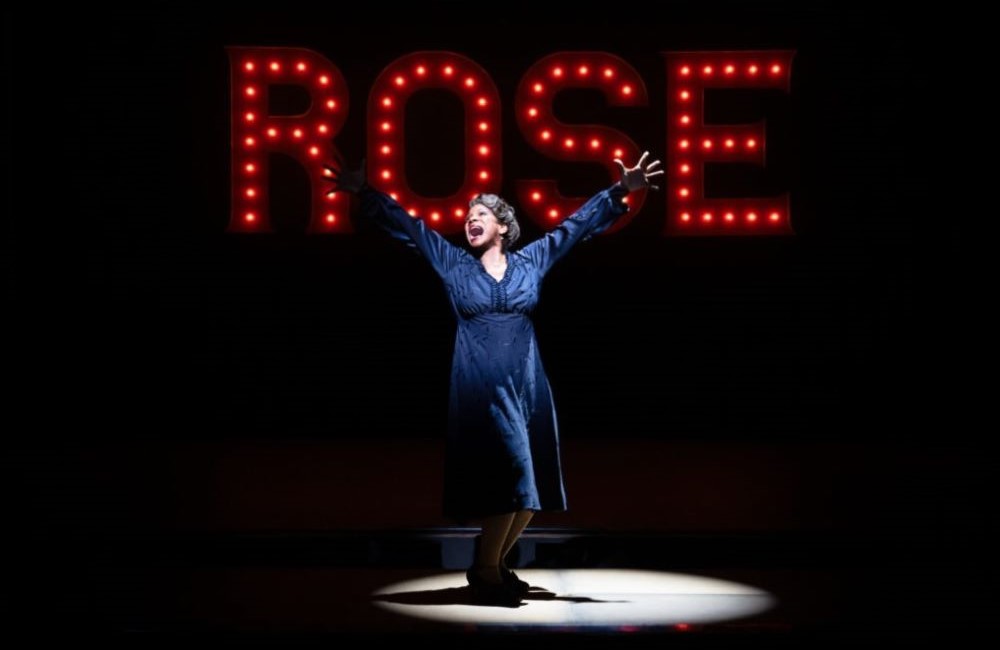

Photo of a scene from the 2025 revival of Evita by Marc Brenner.

One response

-

Wow! It’s a way of looking at/dissecting musicals that’s way above my pay grade, but incredibly interesting. I think that most significantly it’s another example of the limits that accompany all “rules” — probably in most arts fields.

LikeLike

Leave a reply to Tom Freudenheim Cancel reply