A journal for industry and audiences covering the past, present, and future of the musical stage.

On Monday, The New York Times published a story entitled “The Broadway Musical is in Trouble.” It reads, in part: “For one reason or another, the costs of production and operation have become so high that successes have to be fantastically successful and failures have become catastrophes. To meet expenses, ticket prices have to be scaled so high that only a small segment of the public can go to the theatre. It is economically out of bounds for the vast majority of the people. Basically, it is an unsuccessful form of high-pressure huckstering. There is almost no continuity of management and no continuity of employment. The whole business is conducted in an atmosphere of crisis, strain, and emergency. Crisis is the normal state of affairs on Broadway.”

No, wait. Brooks Atkinson wrote that in 1948, roughly one month after the opening of Where’s Charley? (1948); roughly one month before the opening of Kiss Me, Kate (1948); roughly five months before the opening of South Pacific (1949); and roughly two years before the opening of Guys and Dolls (1950). Atkinson was an especially astute and widely respected theatre critic who celebrated vaudeville, of the early 1900s, as “a brilliant form of stage entertainment,” marked by, he said, exuberance, skill, distinction, and “free, bold, crisp, and dynamic showmanship.” He believed that the musical theatre was not an “inferior” form of theatre but, “theoretically,” the “truest” form of theatre, because, he said, “dancing and singing are the basis of the theatre art.” And he noted, upon the conclusion of his nearly four-decade career, which spanned the middle of the 20th century, an artificially controversial and artistically transformative period often referred to as the Golden Age, that “a good musical score without a book becomes valueless.” But let me get us back on track.

The story published on Monday in The New York Times actually reads, in part: “The precarious state of today’s American musical theatre prompts a most troublesome question: is there any future? The expense of producing musicals on Broadway has increased far faster than the rate of inflation, and the real problem is not raising this money but repaying it. The theatre-going public would undoubtedly kick and scream at any increase [in ticket prices], as they always have in the past. But the current cost [of admission], which many onlookers too quickly blame for Broadway’s demise, has been no deterrent to the hundreds of thousands of avid customers who are lining up to keep at least four hit musicals sold out for years to come.”

No, wait. Peter Stone wrote that in 1989, roughly sixteen months after the opening of The Phantom of the Opera (1988); roughly seven months before the opening of City of Angels (1989) and Grand Hotel (1989); and roughly two years before the opening of Miss Saigon (1991). Stone was an especially astute and widely respected book writer whose catalogue includes 1776 (1969), Grand Hotel (1989), My One and Only (1983), and Titanic (1997). “A musical is all structure,” he explained. “Without structure, nothing will work – not the songs, not the dialogue, not the characters. You can fix all those in rehearsal in no time at all. But if you don’t have the structure right, whatever fixing you do on the other things, the musical simply is not going to work.”

In the late 1980s, while serving as the president of the Dramatists Guild, Stone lamented the pervasive ignorance surrounding the book of a musical, which is not dialogue alone, and he lamented the absence of budding book writers. “For one thing,” he observed, “many playwrights don’t understand the form or its possibilities for serious expression. Nor are they particularly interested in a collaboration with other creative artists and the complications that can, and often do, arise from such a relationship.” Relatedly, Stone observed, “At present, what we find in our developmental programs is that the lyricists are writing the books. This is not to say that a lyricist can’t be a fine book writer. However, now what we see is lyricists by attrition – that is, lyricists are doing the book because there is nobody else to do it. And they are not comparable jobs – to be able to do one does not imply automatically that one can do the other.” But let me get us back on track.

The story published on Monday in The New York Times actually reads: “‘Sucker money’ that the ‘angels’ previously provided for the production of legit shows has nearly disappeared…” No, wait. That was the beginning of an article published in Variety in 1928, roughly two months after the opening of Show Boat (1927); and roughly two years before the opening of Girl Crazy (1930). “The legend of ‘angel,’” Variety explained, “as a disguise for the more explanatory word, ‘sucker,’ is that in the olden days when a producer ‘took’ a layman, he would exclaim with the money, ‘Sent from Heaven.’ This was reduced to the word ‘angel’ as taking in more territory and indicating what a sweet and liberal man the provider was estimated to be and also from the same place, Heaven.” Today, we call them co-producers.

Satire aside, the story published on Monday in The New York Times is little more than a trendy and distracting slice of sensationalism, devoid of a purposeful point, a sense of gravity, and an awareness or an understanding of the past. It joins, in being entirely unhelpful to a genuinely serious situation, the incessant, unspecific, and seemingly unserious cries of “the business is broken,” “the shows are too expensive,” “the runways are shorter,” “the running costs are too high,” “we have to start doing business in new ways or we risk losing it,” etc.

In point of fact, Broadway is still composed of disparate products manufactured and operated by independent entities – even if one subscribes to the recently popular and somewhat faulty notion that Broadway is, in and of itself, a brand – and each producer still makes their own creative business decisions, to the extent that they are capable of making such decisions and regardless of whether or not those decisions are informed, and despite all producers adhering, when and where applicable, to the same potpourri of union and real estate restrictions. And producing is one of the major factors in the presently unsteady state of the musical stage. It has been for decades.

In 1989, Peter Stone noted, “A good musical producer is not merely someone with an office who can provide money and a theatre. He or she must be a leader, caretaker, protector, encourager, arbiter, father/mother-confessor, and, in the best of possible worlds, artistic advisor. The great ones were all of these. They didn’t need workshop productions or prepackaged London hits to help them envision their shows. They could read a libretto and listen to the score: that was enough. Today, we don’t so much have musical producers as guarantors of financing.”

One of the other major factors in the presently unsteady state of the musical stage is quality, or the overwhelming lack thereof, stemming primarily from, on the part of artists, producers, and other flora and fauna of the theatre industry and its various pipelines, an unfamiliarity with, a disregard for, and or a misunderstanding of the evolution of the musical theatre, and especially its maturation in the middle of the 20th century, principally in America and specifically in New York, through a decades-long movement, begun about the 1910s and brought to a close in the 1960s, to better the art of musical storytelling – the result of which is not to be confused with the nonexistent rules of musical theatre, and the products of which do not exhibit, despite what one may perceive or have been told, a single sound, a single story, a single structure, or a single style. And, to the detriment of all relevant parties, including audiences, the matter of quality, of skill, of craft is regularly left out of public – and private – conversations concerning costs, marketing, and early closings.

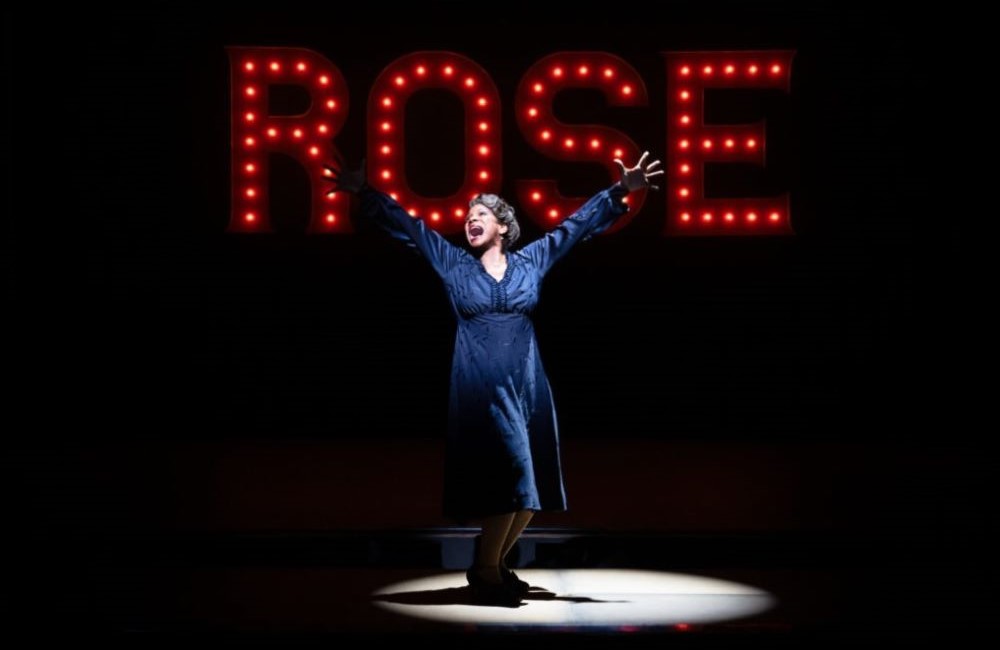

Look no further for evidence than the recent piece in The New York Times, which opens with uncritical, sympathetic, and rather dramatic references to Boop!, Smash, and Tammy Faye: three poorly written properties that each cost upwards of $20 million to produce – by choice. (Boop! nonetheless has fine music by David Foster and jangly orchestrations by Doug Besterman.) A reference is made, as well, to Gypsy (1959), a horrific revival, capitalized at $19.5 million, whose extraordinarily talented star evidently chose to ignore the essence of the character she was playing and the intrinsic nature of the brilliantly written stage show. Indeed, every musical production presented on Broadway is not, contrary to the comforting delusions of some, inherently “well-crafted” and “high quality.”

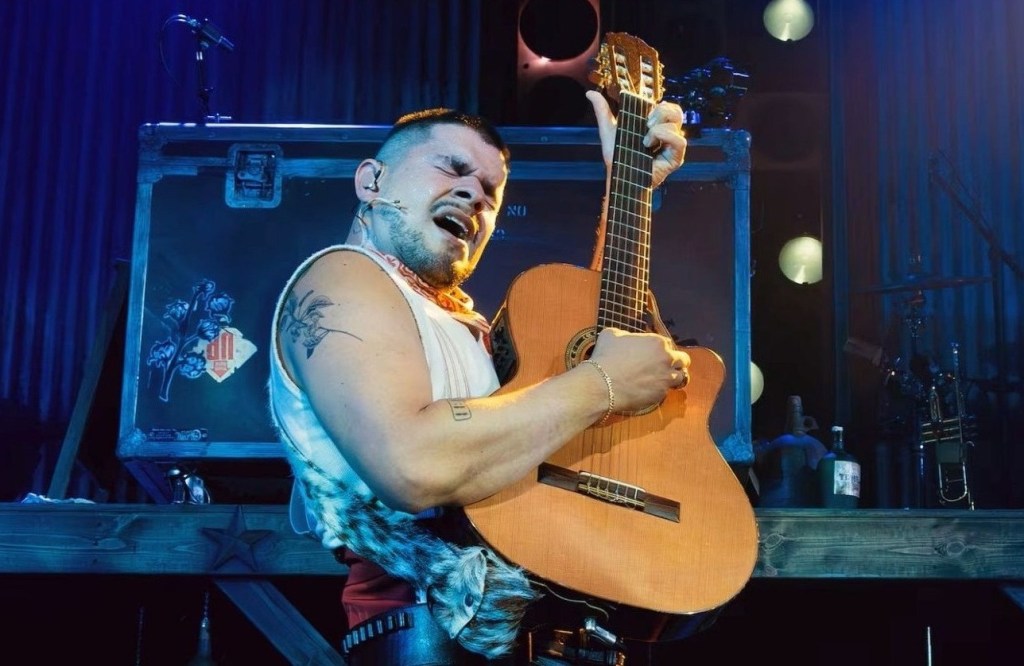

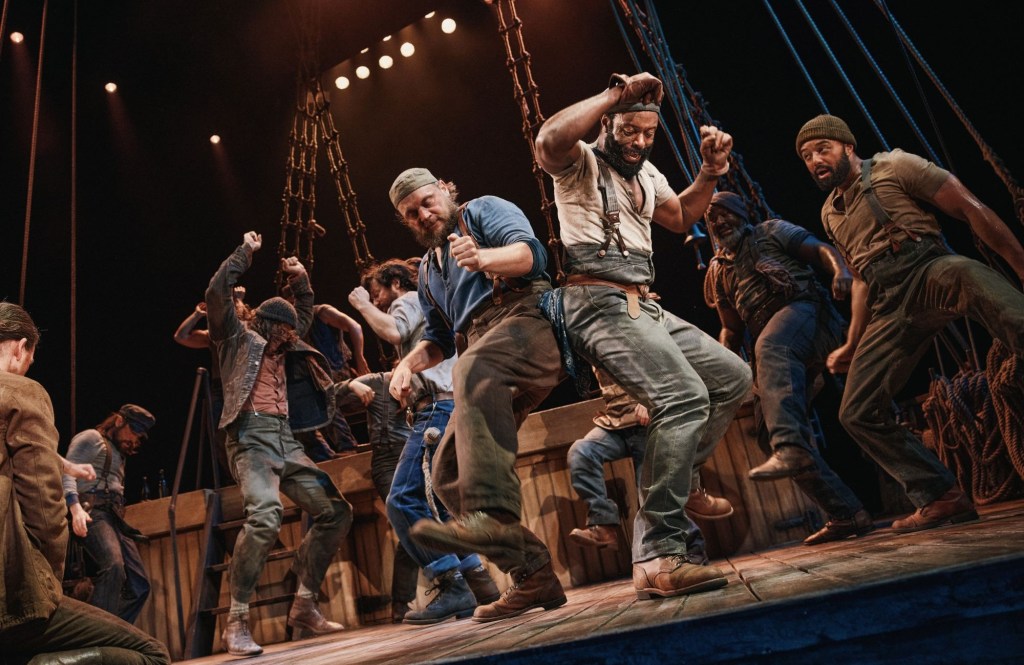

Last week, a friend and colleague told me two salient things: first, that, given the brutality of my Report, I should not walk alone at night in dark alleys; and second, that he is feeling a bit down on the musical theatre these days – which is certainly understandable. The landscape often gives the impression of being artistically baren, the challenges are many, and the challenges have been compounding, especially artistically, for decades. But the future of the musical theatre remains as bright as it has ever been, and we must not give in to the lurid propaganda of any newspaper or individual seeking to snuff it out. Nor must we allow the proliferation of projects we might find suspicious to keep us from plowing forward. Or from making room for the possibility of a happy surprise. (The new production of Damn Yankees registered as bizarre on paper, but it is hugely promising.)

Rising development, production, and operating costs are, in principal, not new, and they are addressable. (An insider piece to that effect is forthcoming.) The receding of the theatre’s footprint in the entertainment marketplace is, in principal, not new, and it is addressable. And the musical theatre, as an art form, is unequivocally not new, which does not negate the possibility of newness and freshness, and every one of us – artist, patron, producer, educator, culture writer, etc. – has the power and capacity to widen our frame of reference, to sharpen our critical and creative faculties, to strengthen our commitment to craft, to understand through focused scrutiny the standards of excellence in musical storytelling that were established in the middle of the last century, and to demand, of ourselves and others, that those standards be met, or at least rigorously pursued, regardless of a particular property’s subject, theme, or musical style. We hold the power, and we must have faith.

Grandiose proclamations of trouble and travesty on Broadway made in part because only two new musicals are opening this fall is, to me, infuriating. Only two new musicals opened in the fall of 1995 – one was based on a film and the other was a songbook revue – but the bruised and battered Rialto is still alive and kicking some thirty years later, and it even managed to turn out Dead Outlaw (2025), Fun Home (2013), and Hamilton (2015) along the way. Not to mention The Band’s Visit (2016), Matilda (2013), and Spring Awakening (2006), et al. Similarly infuriating, to me, is the blanket dismissal of past musicals, especially those written prior to the 1970s and especially without making the distinction between story and craft, by artists and audiences who claim to love the musical theatre; and the blanket dismissal of contemporary musicals by artists and audiences who make the same claim. (And this is to say nothing of the individuals writing for the musical theatre who claim not to “like” musicals.)

Every show must be taken and stand on its own, and every show must close; cost and profitability cannot be effectively examined independent of quality, marketing, and numerous other related factors; individual seasons cannot be effectively examined independent of theatre availability, long runs, and numerous other related factors; and histrionics and historical disregard have no place in formulating serious solutions to complex issues.

The Broadway musical is not in trouble. It dances along, fundamentally, as it has for more than a century, and as it always will: pleasing some, displeasing others, often aspiring to art, and regularly falling short. When, in the distant future, the Earth finally slips off its axis, drops out of orbit, and crashes into the sun, it will do so at 8:05pm ET as the curtain is going up at the Palace Theatre on some fabulous new musical written by some fabulous new talent who once heard of a show called Oklahoma!

Photo of a scene from the Arena Stage production of Damn Yankees by Matthew Murphy and Evan Zimmerman.

Leave a comment