A journal for industry and audiences covering the past, present, and future of the musical stage.

Today is Sunday, and this is a special year-end issue of the Report. It features my favorite musicals (material and production); my favorite moments (from other musicals); my favorite performances; three brief comments concerning scenic designs, the bullshit use of “bold,” and an unavoidable truth; and my favorite reviews. Plus, a quote of the week. The regular sections dedicated to select press announcements from the past week and the upcoming week’s previews and openings will return with next Sunday’s Report – which will have my reviews of Ragtime and Wonder, seen in the final days of December.

QUOTE OF THE WEEK

“And so as the orchestra plays this optimistic theme on a muted trumpet with a little support from the rhythm section, the customers file out of the theatre. Then the musicians pack their instruments in frantic haste and turn their thoughts to wives and children, gambling, food, girl friends, money troubles, or any of the other things which a good, red-blooded union man thinks about. Backstage, the actors wipe off their make-up, leave their glamour hanging in the dressing room, and take their mundane selves to the outer world. The ushers shoo out the last straggling couple and the porter locks the front door. Finally the stagedoor man pulls a switch and the theatre is dark, except for the little pilot light on center stage. Tomorrow is another day.” -George Abbott, from the final page of his memoir

MY FAVORITE MUSICALS (MATERIAL AND PRODUCTION)

I attended more than 50 musicals over the past year – new works and revivals in and bound for New York City – and each, as with every musical, must be taken and stand on its own, albeit within the context of the art form of which it is a part, and understanding the standards of excellence in musical storytelling established in the middle of the last century – not to be confused with the nonexistent rules of musical theatre. Thus, a list of “the best,” “the most,” or “the greatest,” especially with a numerical ranking and or a prescribed number of entries, would, in my view, be quite nonsensical, and even perhaps detrimental to the art.

In lieu of such a list, and to commemorate the past year, I should like to share my favorite musicals, in alphabetical order, with no prescribed number of entries, and taking into account material and production, with quality being the principal factor, for, as previously stated, I care little about what story one wants to tell, where the idea for that story originated, what one wants to do on the musical stage; I care deeply about how one does it.

One of my favorite musicals from the past year is exceptional. One is damn fine, with real weaknesses. Three are damn close to being damn fine, and might even wind up being exceptional, with refinements currently pending. And two of my favorite musicals from the past year are works in progress with incredible promise, and they happen to have the same director.

• Damn Yankees at Arena Stage

This new production of the 1955 musical comedy is bound for Broadway next season, and, with many necessary refinements, it just might develop into a sleek, sparky, and tremendously enjoyable stage show. The Arena Stage production was presented in the round, and, on a macro level, director Sergio Trujillo did a stupendous job of utilizing the space, realizing a fantastic and individual onstage world – a neatly glossy, neon-drenched fantasyland, accented with vibrant colors, sonic fizz, and swift, stylish scenic transitions. The excellent scenic design, by Robert Brill, transformed the intimate theatre into a miniature, multifunctional ballpark, with entrances in each of the four corners of the field, wonderfully theatrical elevators in two corners of the baseball diamond, knee-high video screens wrapping around the perimeter of the playing space, and stadium lighting hanging above it. And lighting designer Philip S. Rosenberg and projection designer Peter Nigrini were no doubt integral to the creation of the glorious, cohesive, tasteful environment. I am grateful for (twice) having experienced Damn Yankees in the round, and I hope that, on Broadway, Trujillo will be able to deliver a proscenium staging that is, on a macro level, as exciting, as definitive, and as intrinsic to the character of the piece. Special mention must be made of music supervisor and arranger Greg Anthony Rassen and orchestrator Doug Besterman, whose combined work on the incidental and dance music elevates the storytelling. Here is my review, including a punch list that the creative team might consider.

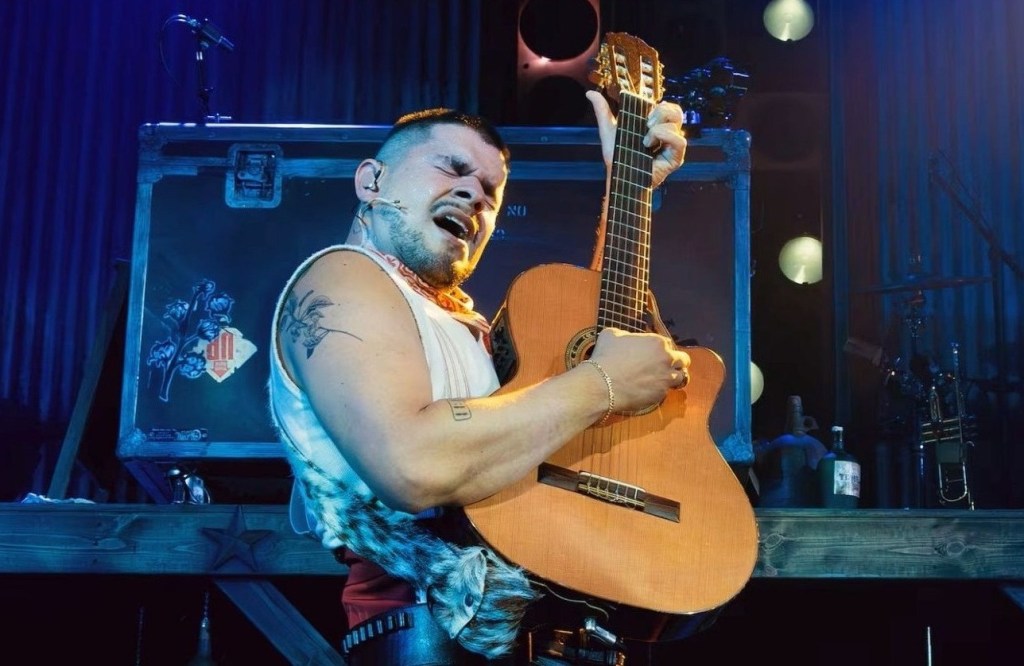

• Dead Outlaw at the Longacre Theatre

This tragicomic American folktale traces the life and death of Elmer McCurdy, from the late 1800s to the 1970s, and it is, objectively, one of the best written new musicals of the 21st century, specifically as carried to completion on Broadway, with several small, significant refinements made following its premiere, in 2024, at the Minetta Lane Theatre. Sadly, I will not be surprised if some or even several years pass before the legitimate musical stage witnesses another new work of such skill, ingenuity, and finish. (Please let me be wrong!) One may, like my husband, certainly dislike the story and the style, but the expert manner, the rigorously detailed manner, the dynamic manner, the blazingly theatrical manner in which the musical has been crafted is undeniable. The storytelling is pristine, the integration of elements is seamless, and the narrative freshness fails to cease, vigorously supported by the exquisite complexity of the composition and the (purposefully) intricate patterning of the plot. Dead Outlaw is the work of Itamar Moses, Erik Della Penna, David Yazbek, and David Cromer, with Dean Sharenow collaborating on the music arrangements and orchestrations. The musical is not flawless, but it is a brilliantly written piece of theatre, and it should be scrutinized by everyone who cares about the art of musical storytelling. Plus, the Broadway production was electric, thrilling, definitive, topnotch, illuminated in a sharp, sensational fashion by lighting designer Heather Gilbert, and adorned with top-of-the-line character work. Here is my review, and here is my reappraisal during the brief run.

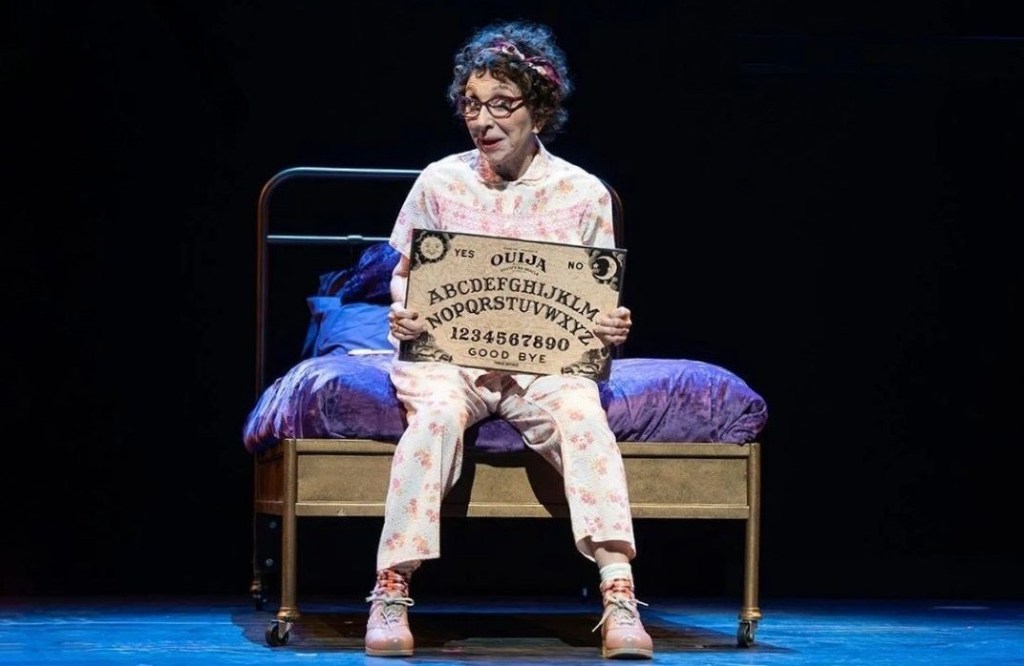

• The Faggots and Their Friends Between Revolutions at Park Avenue Armory

This exceedingly stylish, potentially thrilling storybook revue is based on the 1977 book of fables, and it presents a queer history of human existence, spinning loosely chronological tales, told in the third person with the quality and texture of a fairytale or a children’s bedtime story, about the Faggots, who live in the city of Ramrod. The piece is pregnant with ideas and interest, unfolding in an individual and dynamic world, with a distinctive personality, a point of view, and a sense of theatricality and invention. Most of the lines and lyrics have been lifted from the original text, and the original text has, happily, retained a certain freshness and authenticity, flavored with delicacy, playfulness, and whimsy, even perhaps a sense of innocence, which almost certainly serves to enhance the potency of the poisonous satire and political comment with which the piece is doused. And the music, which runs toward the classical realm, is art-house without being pretentious. The Faggots and Their Friends Between Revolutions is played by 15 actors and musicians on a large, open stage, with the left, right, and upstage perimeters of the playing space lined with tables, lamps, chairs of different looks and sizes, a clothing rack, and an assortment of instruments, and the inspired lighting design, by Bertrand Couderc, is, astoundingly, absent color. But the piece is presently uneven. I hope that creators Ted Huffman and Philip Venables will carry the piece to completion, making the necessary refinements, and I hope that the completed piece will enjoy a wider life. Here is my review, including a punch list that the creative team might consider.

• The Great Emu War at Goodspeed Musicals

This new musical comedy, inspired by actual events, follows the slightly madcap adventures of an eager young emu who goes on migration, discovers wheat, and winds up at the center of the titular war – which, in 1932, found members of the Australian military attempting, unsuccessfully, to eliminate, with machine guns, a massive population of emus. Paul Hodge and Cal Silberstein have, in their work on this particular piece, shown themselves to be intelligent, crafty writers with an understanding of and feeling for the musical stage. The synchronicity of lyric and music is often exhilarating, with a calculated, dynamic interplay that enriches both story and character. The lyrics are frequently of the smarty-pants persuasion, with an inclination toward double meanings, cerebral wordplay, and intricate rhymes. And the dialogue is the stuff of irreverence and cheek, rooted in honesty and seasoned with valuable comic patterns. But cleverness and wit – both palpably present in the material – are not inherently dramatic or dramatically active, nor are they inherent substitutes for dramatic action. And while Hodge and Silberstein have begun to create, for the musical, a buoyant, jack-in-the-box world, they would be well advised to give the world and the narrative composition greater detail and definition. But The Great Emu War is still in development, and it is an incredibly promising piece. Here is my review.

• Operation Mincemeat at the John Golden Theatre

This hugely enjoyable new musical tells the true story of a World War II deception operation conducted by the British government, and it is streaked with intelligence and class, bringing to Broadway a moderately fresh breeze in the way of transformational comedy, with five actors genuinely inhabiting multiple roles. The characters are delicious, individual, and finely etched, the dialogue is frequently crackly, and the neat composition, imbued with a crisp fluidity and a modestly inventive manner, has been deliberately designed to exploit the show’s multiplicitous conceit, cultivating a frequent sense of excitement and play, and shrewdly accounting for character shifts, reveals, reappearances, gender, and type. Plus, the comic situations are executed in a necessarily serious manner, complementing the earned moments of gravity and pathos with which they have been beautifully woven. But Operation Mincemeat is not tremendously well written. Its authors have allowed cheap and seemingly purposeless self-aware commentary to creep into the piece, principally in the second act, which loses a bit of focus and steam, and they have tacked onto the central story a “glitzy finale” that, for the most part, pierces a literal and figurative hole in the generally well-formed world of the show. Some of the stage business is not rooted in situation and character, notably two labored telephone bits. Certain laugh lines are forced. Certain characters and subplots simply dematerialize. And the derivative music is the musical’s weakest link. But Operation Mincemeat has much more in its favor, including a modicum of skill, enthusiasm, theatricality, and finish, and I look forward to a second visit. Here is my review.

• Senior Class at Olney Theatre Center

This new musical comedy centers around a group of high school students at the Manhattan School (of the Arts) who find themselves unable to license My Fair Lady when their budget is unexpectedly used to purchase a new bus for one of the school’s sports teams. Thus, the students resolve to perform the show’s public domain source material, Pygmalion, with original songs. Senior Class has a number of assets. The original idea is strong, with a moderately layered and involving plot that naturally lends itself to an array of boisterous and serious incidents. The characters are colorful, and almost all of them are well on their way to being sharply and individually drawn. The dialogue is often clever and punchy, and it generally seems to have been tailored to the attendant personalities. The comedy is regularly rooted in situation and character. The world of the show has a real grounding in reality and a hint of individuality that, with continued growth, will help to set the piece apart from other scholastic enterprises. And some of the devices that have been employed, in the service of the storytelling, are fun and exciting, suggesting a valuable sense of theatricality and purposeful play on the part of the creative team. That said, Senior Class currently faces three large issues: the patterning of plot, the internal focusing of scenes, and the purposing and spotting of songs, which includes the lack of specificity in the lyrics. But the musical is still in development, and it is incredibly promising. Here is my review.

• Soon at East Village Basement

This revivifying new musical, by Nick Blaemire, centers around a young woman who refuses to leave her apartment due to the imminent end of the world – though an eleventh-hour revelation alters the circumstances of the story, which has little to do with apocalyptic climate change. Soon has only four characters and a thin shred of plot, but it is emotionally, intellectually, and dramatically expansive, and it bubbles with theatricality. The characters are complicated, flesh-and-blood human beings, with a certain emotional fragility and or shades of discontent underpinning their comic quirks. Most of the scenes, including those with song, unfold organically and propulsively, with a quiet dramatic tension sustained almost throughout the show, and most of the scenes crackle, with several generating fireworks in their kinetic combination of personalities ricocheting off one another in a seemingly spontaneous manner. And if the juicy, playful dialogue tends to outdistance the score, the score nonetheless contains a handful of incredibly fine musical numbers resolutely fashioned for the stage. Soon is imperfect, and it would benefit from a number of small refinements, especially in terms of composition and mechanics. Plus, the East Village Basement production was unsatisfactory. But the musical contains a mass of material meat and a human touch, and it demands a wider life, on a proper theatrical stage, with a proper theatrical staging. Here is my review.

MY FAVORITE MOMENTS (FROM OTHER MUSICALS)

The balance of the musicals presented last year – and seen by me – were, from a standpoint of craft, completeness, theatricality, and dramatic effectiveness, mixed to poor, taking into account material and production. (Many were disastrous.) But several contained individual moments that were especially fine. Here are my favorite moments of the sort, again placing no cap on the number of entries.

• The Finger Pointing in The Bedwetter

The Bedwetter, a new musical based on the memoir by Sarah Silverman, might have been my most frustrating theatre experience of the year, for it is wildly out of sorts, despite an insanely fine collection of principal characters; despite a profitably theatrical, beautifully nutty story into which the insanely fine collection of principal characters have been tossed; despite a would-be fantastic composition, shrewdly and purposefully echoing a 1970s variety show, with a quick-cut, multi-locale collection of scenes, fantasies, interludes, and live and projected television sequences; and despite appearing to want to have a deliciously individual, eccentric, and foul-mouthed personality. (The creative team seems afraid to embrace the musical’s innate nature, preferring instead to try for the tepid quirkiness of Kimberly Akimbo.) The Bedwetter needs much work. But, late in the evening, a chic, gin-flavored grandmother, played by Liz Larsen, responds to a hopeful inquiry from her granddaughter, the title character, with a simple gesture: her arm lifts, her hand undulates ever so slightly, and her index finger engages, extends, and lands, in an effortlessly punctuated fashion, pointing to the title character’s attractive older sister, instead of the title character. It is an invigorating, well executed comic moment, fairly well set up over the course of the show, and lasting all of three seconds. I genuinely hope that The Bedwetter comes back with a vengeance.

• The First 25 Minutes of Chess

This new adaptation of the 1988 musical is a numbing theatrical travesty, and the musical’s score is, contrary to popular belief, not great – if, by great, one means well crafted, distinctive, and dramatically effective. The songs, especially in terms of the music, which has a certain vitality, may be wonderfully invigorating and hugely profitable in the popular-music sphere, for concert, radio, and recording, and I have freely admitted, in my review, to enjoying many of the songs from Chess under such inherently different circumstances, but the songs, even the introspective soliloquies, wilt on the theatrical stage, largely failing to serve the story, situations, and characters for which they have been written. Nonetheless, the first roughly 25 minutes of the musical, as revised by Danny Strong and directed by Michael Mayer, are intriguing and occasionally enlivening and, on the whole, extraordinarily well staged. Note, in particular, the introduction of the new conceit, the stylish voyeurism and Greekness of the gray-suited ensemble, the introduction of each of the principal characters, the stormy solo for one of the leading men, and the two production numbers led by featured actor Bryce Pinkham, especially “The Arbiter,” with which the first 25 minutes of the musical culminates, and after which the musical runs immediately and almost continuously downhill. I was genuinely shocked by how interested I was in – and by how excited I was by – the musical up to and including Pinkham’s exhilarating corker, excusing its dramatically muddled dance break. In fact, I would welcome revisiting those first 25 minutes of the musical, despite the many blunders contained therein, but the remaining 135 minutes will likely prevent me from doing so.

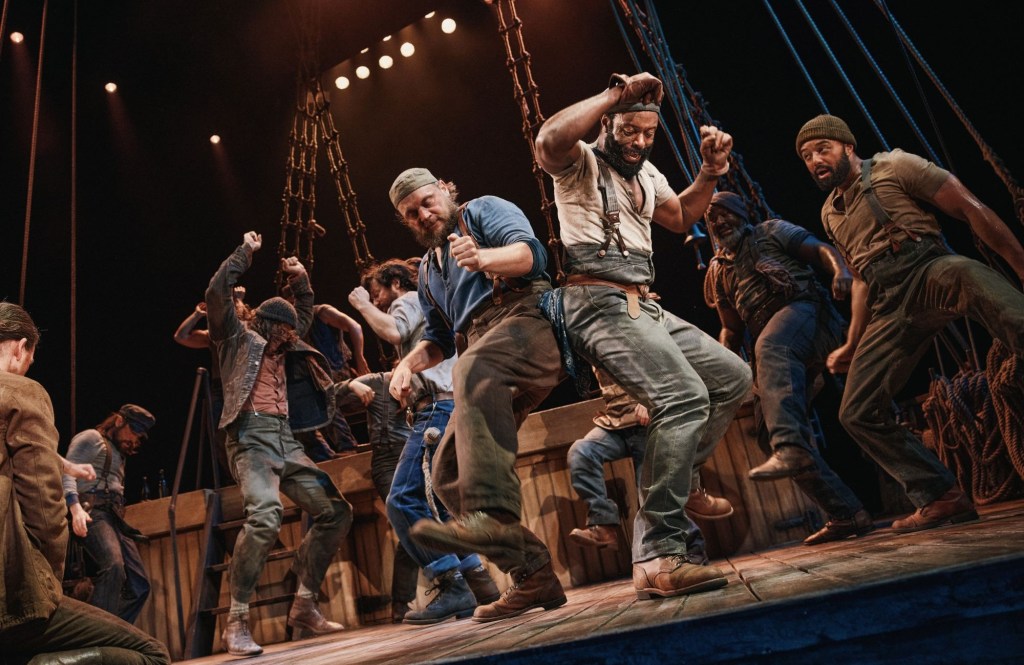

• The Stage Pictures in Floyd Collins

Floyd Collins is set in Barren County, Kentucky in 1925, and it attempts to dramatize the rescue effort, media circus, public spectacle, and familial distress resulting from a young cave explorer getting trapped underground. This revival of the 1996 musical unfolded on an open stage, permanently adorned with an upstage cyc, and tastefully accessorized, from time to time, with traps, long tilted blocks protruding from and leading under the stage, suspended wooden beams, benches, ropes, lanterns, and a few strands of lights. The piece was given a superb physical staging by Tina Landau, who realized a succession of stunning, story-driven stage pictures. A second-act solo, for instance, found Floyd’s younger brother storming downstage center in a rectangular slash of sidelight, backed by an isolated and dimly lit tableau. An effort to pull Floyd out of the cave, with a rope, wrapped around the entire stage in opposition. A failed effort to dig an underground shaft found two men in a shallow trap stage left clinging to a vertical rope and looking upwards to the surface, the supervisor on a tilted block upstage center looking down into the shaft, and Floyd affixed to a stage right slab, with each of the three areas isolated in downlight. A reporter briefly materialized at the stage left proscenium in a slat of light. A photographer briefly materialized in the stage right vom to snap a picture of Floyd’s grieving relatives. A pin spot snapped to a sculpted wash of the full stage. A downstage spot was played against a stage-width silhouette. And heightened colors adorned the carnival and dream sequences. Nearly every moment in the production was remarkable, specifically in terms of the vibrant and active staging of the story, and, under the circumstances, I have decided to list the production’s many moments as one. Special mention must be made of scenic designer dots and lighting designer Scott Zielinski.

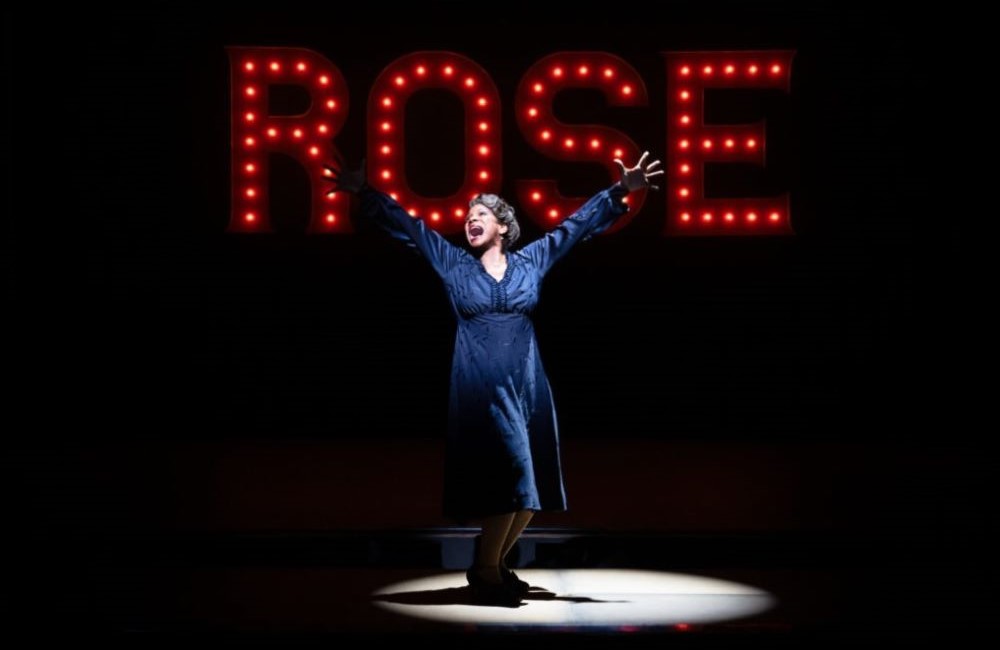

• “This is Not the Way” in Sherie Rene Scott’s The Queen of Versailles

The Queen of Versailles, about Orlando billionaire Jackie Siegel, might have been a thrilling theatrical affair, and Sherie Rene Scott, who served as special standby to star Kristin Chenoweth, might have been a thrilling theatrical Jackie. Scott is an incredible – and peculiar – stage star with a powerful, glistening voice, and she has a certain way with the union of words and music that is wonderfully theatrical and deeply affecting, her gut-busting vocal performance, with lines sometimes luxuriously liquid, living in the lyric and soaring on the same. She has, as well, a certain way with comedy. Though Scott naturally had not the time to flesh out and refine her performance in The Queen of Versailles, her performance showed the promise of greatness, peppered with several exciting moments and hints of detail, complexity, and purposeful play, and her delivery of the first-act finale, “This is Not the Way,” was volcanic – an exhilarating theatrical moment I shall not soon forget, despite the material faults.

• “Yeast of Edith” in Slam Frank

Slam Frank is an appallingly juvenile affair, marked by a serious lack of skill and a seriously hoary framing device. (A community theatre troupe presents the story of Anne Frank through an ultraprogressive, radically inclusive lens, reimagining the historically Jewish figures as gay, nonbinary, pansexual, feminist, Latina, neurodivergent, etc.) But a number of the underlying ideas are potent, if poorly executed, and, roughly 20 minutes into the proceedings, Anne Frank’s mother, Edith, delivers a poetic monologue that is very strong, with a button that is dynamite.

Separately, I want to acknowledge the opening of Redwood, the second-act opening of Saturday Church, and the prologue of Take the Lead. The first was a complex sequence that wove together dialogue and song in an attempt to build, for the audience, the central figure’s entire backstory, by way of fractured memories actively occurring while she is driving from New York to California. The second was a showpiece consisting of clacking fans and a roll call. And the third found the high school students and ballroom dancers of the story intermingled onstage in fixed positions, with each body introduced individually, courtesy of a personal choreographic flourish, an isolated pool of light from a down or side special, and a single orchestral accent, which became a double accent as the introductions continued. Then, the show’s central figure stepped through the crowd and philosophized about dance in a direct address to the audience, underscored with pulsating music. The idea behind these three moments from these three musicals was exhilarating, even though the execution, in each case, was faulty.

MY FAVORITE PERFORMANCES

Several performances from the past year were quite fine. My favorite are almost certainly those of Carmen Cusack and Nik Walker in Bull Durham; Bryce Pinkham in Chess; Bryonha Marie in Damn Yankees; Jeb Brown, Andrew Durand, Dashiell Eaves, Julia Knitel, Ken Marks, and Thom Sesma in Dead Outlaw; Kit Green in The Faggots and Their Friends Between Revolutions; Natalie Hodgson, Zak Malone, and Zoë Roberts in Operation Mincemeat; and Justin Cooley in The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee. And a word must be said for Chad Doreck, a charismatic, boisterous entertainer who, in 44, bounced around the stage of the Daryl Roth Theatre with a certain skill, an infectious zest, and a sense of purposeful play, giving audiences a hint of the spry, thumping burlesque that the dreary musical might have been.

A STORY IS NOT ENOUGH

Buena Vista Social Club, Lights Out: Nat “King” Cole, The Queen of Versailles, and Redwood might have been extraordinary musicals, for each is built upon an exceedingly potent story, rich with theatrical possibilities. But a story – potent or otherwise – is not enough. The effectiveness, the distinction, the completeness of a stage musical is almost entirely a matter of how the story is told, how the story is crafted for the stage – which necessarily involves an assortment of factors, like character, incidents, structure, composition, style, focus, language, and point of view. Not to mention the synchronicity of elements: dialogue, lyrics, music, including arrangements and orchestrations, and staging, including design. Plus, detail and rigor and, one hopes, theatricality and showmanship and imagination. Indeed, a story is not enough.

Sadly, this unavoidable truth often seems to go unrecognized – or to be disregarded – by members of the industry, at large, and its various pipelines, but this unavoidable truth was reinforced time and again over the past year, especially by these four artistic misfires, and, to a lesser extent, by Real Women Have Curves, Take the Lead, and Wonder, among others. Buena Vista Social Club has nonetheless managed to survive – though not necessarily thrive – commercially, because the story is, unfortunately, merely an excuse for the already-popular Afro-Cuban music, performed onstage by a crack band. (Imagine the musical Buena Vista Social Club might have been if the story was skillfully told!) In the case of Lights Out: Nat “King” Cole, The Queen of Versailles, and Redwood, like most stage musicals, the story was the thing.

BIGGER IS NOT NECESSARILY BETTER

Most of the musical productions from the past year had a scenic design that was notably less than extravagant, and I should like to salute, in particular, the incredibly fine work of Derek McLane on Bull Durham, Robert Brill on Damn Yankees, Arnulfo Maldonado on Dead Outlaw, Riw Rakkulchon on Mexodus, and Ben Stones on Operation Mincemeat. Each of these eminently attractive designs served the attendant storytelling with aplomb, proving highly functional, emitting the fragrant aromas of taste and ingenuity, and making active contributions to the character and, excepting Mexodus, the composition of the respective offering. Each is a potent reminder that bigger is not necessarily better, that economy and imagination can be spectacular, and that limitations can be a creative boon. That said, the extravagant scenic design, by Dane Laffrey, for The Queen of Versailles was similarly fine, simply poorly exploited. And a set is not designed in a vacuum, so the directors and fellow designers of these six shows must be acknowledged.

THE BULLSHIT USE OF “BOLD”

Nearly everything, of late, seems to be branded “bold.” Furthermore, in a rather dangerous development, the increasingly meaningless term has breached the bounds of sensationalistic marketing, used by production companies in the promotion of a particular project, to become a word of praise, used by artists and audiences as evidence of a particular project’s quality or worth. But let us be clear: “bold” is not a synonym for skillful, engaging, dramatically effective, or worthwhile. And no show gets extra points for being “bold,” or for being proclaimed as such. Try being good.

(THESE ARE A FEW OF) MY FAVORITE REVIEWS

My purposefully brutal reviews have become something of the centerpiece of the Report, and I want to reiterate that my reviews reach beyond any one show, with detailed creative discussions and artistic analysis, stemming from objective observations, that have implications for any number of projects, while speaking specifically to the project at hand. Here are my favorite reviews from the past year.

• The Baker’s Wife at Classic Stage Company

• The Bedwetter at Arena Stage

• Bull Durham at Paper Mill Playhouse

• Ceilidh at M&T Bank Exchange

• Chess at the Imperial Theatre

• Damn Yankees at Arena Stage

• Is Dead Outlaw One of the Best Written New Musicals of the 21st Century?

• The Faggots and Their Friends Between Revolutions at Park Avenue Armory

• Floyd Collins at the Vivian Beaumont Theater

• The Great Emu War at Goodspeed Musicals

• In Clay at Signature Theatre

• Mexodus at the Minetta Lane Theatre

• Operation Mincemeat at the John Golden Theatre

• The Queen of Versailles at the St. James Theatre

• Real Women Have Curves at the James Earl Jones Theatre

• Redwood at the Nederlander Theatre

• Senior Class at Olney Theatre Center

• Smash at the Imperial Theatre

• Soon at East Village Basement

• Stephen Sondheim’s Old Friends at the Samuel J. Friedman Theatre

• Take the Lead at Paper Mill Playhouse

• The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee at New World Stages

• Two Strangers (Carry a Cake Across New York) at American Repertory Theater

• The Untitled Unauthorized Hunter S. Thompson Musical at Signature Theatre

The other professional productions that I attended last year are All the World’s a Stage, Bat Boy, Beau, Boop!, Buena Vista Social Club, 44, Goddess, Hard Road to Heaven, Heathers, The Jonathan Larson Project, Just in Time, The Last Bimbo of the Apocalypse, The Last Five Years, Lights Out: Nat “King” Cole, Night Side Songs, Oratorio for Living Things, Picnic at Hanging Rock, Pirates! The Penzance Musical, Ragtime, Rolling Thunder, Romy and Michele, Safe House, Saturday Church, Schmigadoon!, The Seat of Our Pants, Show/Boat: A River, Slam Frank, Small Ball, Wonder, and A Wrinkle in Time. (My reviews of Ragtime and Wonder will be published in next Sunday’s Report.)

I was unable to attend Always Something There…, The Apple Boys, Co-Founders, Dolly, 42 Balloons, fuzzy, The Gospel at Colonus, The Heart, Huzzah!, I and You, Joy, Let the Good Times Roll, Macbeth in Stride, Mamma Mia!, Millions, Mythic, Nobody Loves You, Purple Rain, Regency Girls, Reunions, Revolution(s), Stompin’ at the Savoy, Sunny Afternoon, 3 Summers of Lincoln, Vape!, When Elvis Met the Beatles, and Working Girl, among others.

Photo of Collin Shay in The Faggots and Their Friends Between Revolutions by Stephanie Berger.

Leave a comment