A journal for industry and audiences covering the past, present, and future of the musical stage.

High Spirits, I Apologize (But Not Really!), Cutting is Probably Not the Answer, Manon!, and More

Today is Sunday, and this week’s Report features a review of High Spirits; a quick take on Manon!; “I Apologize (But Not Really!)”; and “Cutting is Probably Not the Answer, Nor Does Shorter Necessarily Mean Tighter.” Plus, a quote of the week; select press announcements from the past week; and a list of the upcoming week’s previews and openings.

QUOTE OF THE WEEK

“The lyricist, like any artist, cannot be neutral. He should be committed to the side of humanity. He should be concerned for the rights, potential, and dignity of his fellow man. He should also be able to express these ideals with a proper concern for the rights of the human ear, the potential of the human brain, and the dignity of the English language.” -E.Y. Harburg

HIGH SPIRITS AT NEW YORK CITY CENTER

High Spirits, a concert presentation of the 1964 musical, is currently playing a two-week engagement at New York City Center. It has a book, lyrics, and music by Timothy Gray and Hugh Martin and direction by Jessica Stone, and it is infuriating dreck, begging the question: do Jenny Gersten, Clint Ramos, and Mary-Mitchell Campbell, in their capacity as the leaders of City Center’s Encores!, have any critical faculties, creative know-how, or understanding of the musical stage? Jeanine Tesori is the outfit’s “creative advisor.”

The score is pathetic: intermittently flavorful and, almost from overture to exit music, dramatically useless! Exactly one number, “Home Sweet Heaven,” has been endowed with a solid dramatic foundation, a definite dramatic purpose, and a definite theatrical drive – and Campbell, who serves as music director, has sabotaged it, serving-up the slinky second-act lament at a relentlessly brisk tempo, better suited to Sammy Davis, Jr. or Kay Starr, that prevents any sort of purposeful play with the fine listicle lyric. (A delicious Gertrude Stein lick twice sputters forth and dies.) Plus, Stone has trapped its interpreter, Katrina Lenk, on the upper-level landing of the sparse set, squeezing the actor in front of the large orchestra. And concert adapter Billy Rosenfield has shat on the lead-in with a hoary, moment-breaking retort from the reader, for the concert, of the stage directions: Noël Coward, upon whose play, Blithe Spirit, the musical is based. Rosenfield has also inserted, for the concert, an absurd reprise of “Home Sweet Heaven,” performed by two different characters, at the close of the show. Most of the other songs in the score are essentially pop songs, suggested by certain situations or circumstances; they do not actually serve said situations or circumstances in a theatrical setting as part of a continuous dramatic narrative.

The book is similarly pathetic, in character, structure, and routine, including the spotting, purposing, and allocation of song. The book is pathetic even in dialogue, notwithstanding a few sharp exchanges buried within pages of dullness. Each of the four times – twice in each act – that the show shifts away from the Condomine residence to Madame Arcati – a role that has been inexpertly promoted to a top-line principal – the eccentric medium delivers a song, without fail and for no clear dramatic reason. Even “Talking to You,” which has a marginally personal lyric and a profitable vaudeville bent, finds Madame Arcati having to, out of nowhere, set-up herself – and the moment – with an inquisitive, presentational verse, before shifting her focus to a Ouija board, to which the body of the song is delivered, accompanied by a soft shoe.

Madame Arcati was originally played, in 1964, by Beatrice Lillie, a famed creature of original revue, but the character’s four interludes, almost specialties, are not definitively or profitably designed – nor is the musical definitively or profitably designed – with an inclination toward the same. (A definite inclination toward revue might have been terrific.) Plus, three of said interludes involve the ensemble of 1960s beatniks, who, to make matters worse, have not been effectively incorporated into the proceedings, for they exist almost exclusively as an appendage of Madame Arcati. (The act one finale is the sole exception.) The resulting narrative scissure is neither definitive nor profitable, and the poorly defined ensemble’s use as stage hands does not help – at least not their current use as stage hands. (Gower Champion, a seismic talent, doctored the original production.)

The first act ends with three songs almost back-to-back, separated by only a dozen or so lines of dialogue that do not support or effectively ramp-up into their respective song. And all three songs are sung – entirely, principally, and in half – by the same character! (This is the original script!) “Something Tells Me” nonetheless has an attractively ethereal nature, and “I Know Your Heart” has a brief counterpoint lyric that is active, with a clear dramatic intent.

The three secondary characters are complete afterthoughts. The stakes are nearly nonexistent. The motivations and relationships are largely superficial, due in part to the malfunctioning lyrics and music. The instances of magic and physical comedy, given the narrative circumstances, carry, in principle, the possibility of much fun, in a fully staged production, but the narrative circumstances, as originally written, are wildly undernourished, rendering the instances of magic and physical comedy pretty near empty. (Attractive garnish absent a main dish.) And one wonders why, for the concert, Rosenfield has Coward suddenly take on the role of Dr. Bradman. Especially without any meaningful moment in which his transformation occurs.

The entr’acte is bizarrely routined, and, like the overture, it fails to develop into a powerful statement. Even the successive pullbacks on “Home Sweet Heaven” in the overture – presumably designed to be climactic – come across as bland and perfunctory, under Campbell’s baton, and they generate no tangible payoff. Campbell is responsible, as well, for some sloppy entrances. And the orchestrations are neither here nor there, despite a couple of good saxophone moans and a smattering of percussion toys. (This is not Ralph Burns!) Even one of the show’s authors has referred to the show’s orchestrations, by Harry Zimmerman, as “ordinary.” (Luther Henderson, an ace music man, is understood to have scripted the overture.)

Stone, in her program biography, calls High Spirits an “incredible gem,” and she is categorically mad. Or without knowledge or taste or gravity or any sizable frame of reference. And while there is something to appreciate in her decision to treat the concert as a concert, with scripts in hand and minimal props, her staging is nonetheless rough. And Ellenore Scott’s choreography, a jumble of battements, tree branches, bike handles, and Bob Fosse, basically devoid of character, theatricality, and an individual point of view, is abysmal. And this is with the benefit of a “Choreography Development Workshop!”

In addition to Lenk, the principal cast includes Andrea Martin, Steven Pasquale, and Phillipa Soo, who similarly offers something to appreciate in the combination of speed and verbal clarity with which she flings about her lines. And Lenk offers something to appreciate in the way in which she has begun to incorporate her costume, by Jennifer Moeller, into her characterization.

Perhaps this agonizing affair will serve as a wake-up call to the industry, fueling a reeducation, a reassessment, an artistic revolution, and therein find its worth. Regardless, High Spirits closes on February 15. Good riddance.

I APOLOGIZE (BUT NOT REALLY!)

Last Sunday, I recognized 30 musicals, nine book writers, and 18 songwriters who have taken up permanent residence in my heart, and who continue to fuel my love of the musical stage, and I recognized 28 additional authors and shows that continue to inspire. On Monday, I received a message from a reader who was befuddled by the absence, from every one of my lists, of composer Harold Arlen. And I must, therefore, apologize. (But not really!)

Arlen was a prolific composer with a stage background and a propensity of pop. He played in vaudeville, before the institution’s demise, as an onstage pianist for both Lyda Roberti and Frances Williams; he wrote for the Cotton Club in the 1930s; his films include Cabin in the Sky (1943) and The Wizard of Oz (1939); and his stage musicals include Bloomer Girl (1944), House of Flowers (1954), St. Louis Woman (1946), and You Said It (1931). One of his most frequent collaborators was E.Y. Harburg, who described Arlen’s style as a “synthesis of Negro rhythms and Hebraic melodies.” Arthur Schwartz described Arlen as “a Gershwin derivative, but mighty good.” Some great Arlen songs that immediately spring to mind are: “Buds Won’t Bud,” cut from Hooray for What! (1937); “Coconut Sweet,” from Jamaica (1957); “Down with Love,” from Hooray for What! (1937); “Get Happy,” from Nine-Fifteen Revue (1930); and “Satan’s Li’l Lamb,” from Americana (1932).

Indeed, I have a great fondness for Arlen, but he has not taken up permanent residence in my heart, nor is he one of my primary sources of inspiration. And the same can be said for composer Milton Ager (“Louisville Lou”), book writer, lyricist, and composer Marc Blitzstein (The Threepenny Opera), book writers and lyricists Betty Comden and Adolph Green (Wonderful Town), composer George Gershwin (Of Thee I Sing), composer Ray Henderson (Strike Me Pink), sketch writer and lyricist Arnold B. Horwitt (Plain and Fancy), composer Jerome Kern (Show Boat), lyricist and composer Jonathan Larson (Rent), book writer Arthur Laurents (Gypsy), composer Turner Layton (“After You’ve Gone”), book writer Neil Simon (Little Me), and composer Charles Strouse (Golden Boy).

Likewise Bob Merrill, the lyricist and composer of Carnival (1961), New Girl in Town (1957), and Take Me Along (1959). Some of his nontheatrical novelty pop songs, written primarily in the 1950s, are delicious. Listen, in particular, to “The Key to My Heart,” “Mambo Italiano,” “Ooh! Bang! Jiggily! Jang!,” and “Sweet Old Fashioned Girl.”

Likewise Jimmy Johnson, the composer of Keep Shufflin’ (1928), Messin’ Around (1929), and Runnin’ Wild (1923). Johnson collaborated with lyricist Henry Creamer on the score for the Ciro nightclub revue The Creole Follies (1926), which featured “If I Could Be with You (One Hour Tonight),” and he wrote several symphonic jazz compositions, including “Victory Stride” and “Yamekraw,” which he performed in Messin’ Around.

Likewise Vee Lawnhurst, the composer of several nontheatrical pop songs, primarily from the 1930s. Among my favorite are “Alibi Baby,” “Cross Patch,” “The Day I Let You Get Away,” “I’d Rather Call You Baby,” “Mutiny in the Parlor,” “No Other One,” “Please Keep Me in Your Dreams,” and “The Same Old Line.” Lawnhurst also composed the unproduced magic musical Abracadabra. Her primary collaborator was lyricist Tot Seymour, and the two were advertised as “the first successful team of girl songwriters in popular music history.”

Likewise Joe McCarthy, the lyricist of theatrical pop songs like “I Love Her (Oh! Oh! Oh!)” and “You Made Me Love You.” McCarthy also wrote a couple of early, artistically progressive, but still immature stage musicals, like Irene (1919) and Oh, Look! (1918), which nonetheless spawned “I’m Always Chasing Rainbows.” (Here is a contemporaneous recording of the show’s star, Harry Fox, performing the number.)

Likewise Ira Gershwin, the lyricist of Girl Crazy (1930), Lady in the Dark (1941), Of Thee I Sing (1931), and Oh, Kay! (1926). Often overlooked are Gershwin’s several snazzy lyrics written for original revues, like Americana (1926) and Life Begins at 8:40 (1934), whose score Gershwin coauthored with E.Y. Harburg and Harold Arlen.

And I have a great fondness for lyricist and composer Stephen Sondheim, about whom a different reader confronted me on Wednesday, befuddled. But Sondheim has not taken up permanent residence in my heart, nor is he one of my primary sources of inspiration – though five of his shows have and are, per last Sunday’s Report.

My list of great fondnesses is probably a little longer. But you can be certain that many names have been deliberately omitted. Cue the messages!

CUTTING IS PROBABLY NOT THE ANSWER, NOR DOES SHORTER NECESSARILY MEAN TIGHTER

I am quite tired of hearing members of the industry and culture critics advise, often casually, the producers and the creative team of a new musical to eliminate 15 or 20 minutes of said musical, if said musical currently feels long and or does not quite work. I am similarly tired of hearing members of the industry and culture critics refer, automatically, to a shorter version of the same show as tighter. Just because a show is shorter than it used to be does not mean that it is tighter. Or dramatically effective. Or distinctive. Or complete. And if a new musical currently feels long and or does not quite work, cutting is probably not the answer. Surely not arbitrarily cutting 15 or 20 minutes. Indeed, the answer to a new musical that currently feels long and or does not quite work is almost certainly a combination of focus, efficiency, detail, and fullness, principally in terms of the material. Stop advising arbitrary cuts, and, to borrow a phrase from the ad campaign for American Beauty, look closer.

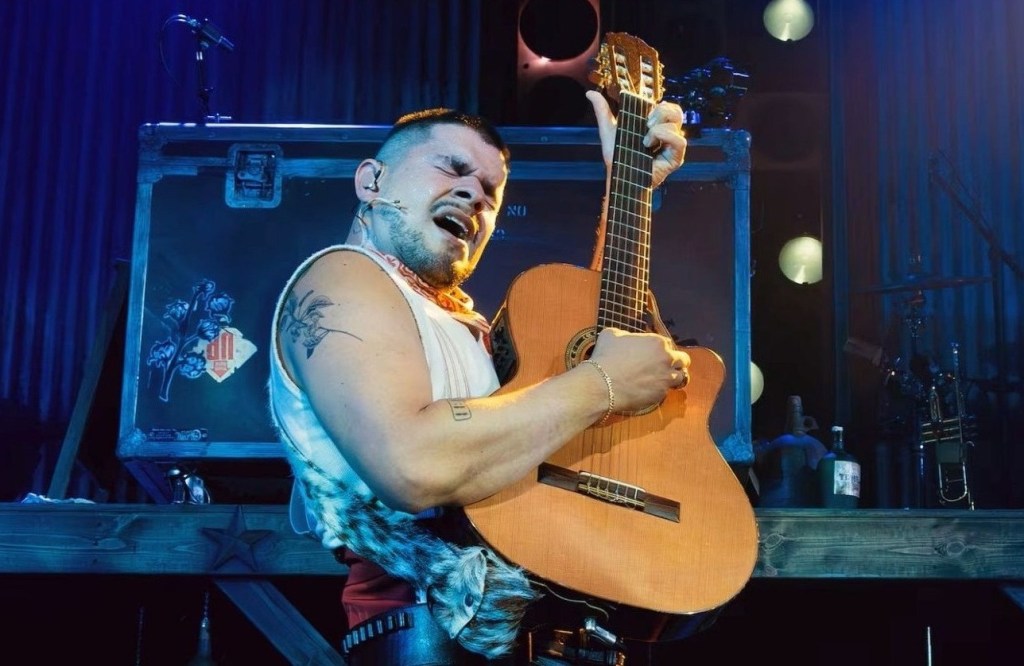

MANON! AT THE SPACE AT IRONDALE

Manon!, a new “musical theatre” adaptation of the 1884 opera, is currently playing a three-week engagement at the Space at Irondale under the auspices of Heartbeat Opera. It has a book and lyrics by Jacob Ashworth and Rory Pelsue, from the original libretto by Henri Meilhac and Philippe Gille, and music by Jules Massenet, newly arranged by Dan Schlosberg. Manon! runs roughly 105 minutes without intermission, where the original unfolded in five acts, and it is, as a piece of theatre, poor.

But the music, taken independently, separate and apart from the offering’s theatrical aims, is frequently savory, peppered with several gorgeous motifs, and Schlosberg has, happily, realized a certain sonic fullness in his fine orchestrations, for eight musicians. The seven actors have strong vocal instruments, with perhaps one exception, and with the vocal instrument of Emma Grimsley, who plays Manon, being especially strong. And the diction, almost across the board, is divine.

The Space at Irondale is a crumbling multipurpose performance venue in Brooklyn, and formerly a 19th century Sunday school, but the production of Manon!, as directed by Pelsue, aspires to tasteful grandeur, unfolding on a rectangular black deck, with a reflective surface and a neon light strip lining the perimeter. The deck is raised roughly one foot off the floor, and it is, initially, shrouded with a sheet – which is dramatically torn away at the top of the show. Eight ornate chandeliers are raised and lowered, over the deck, during the course of the show. Snow drifts down, onto the deck, at the end of the show. And, at one point, a runner is torn out of a trunk and unfurled diagonally across the deck, before being torn offstage at the end of the scene. (Alexander Woodward designed the set.)

One can surely appreciate the intent with regard to the environment and the attendant scenic gestures, but the execution is faulty, largely lacking in definition, continuity, consistent, deliberate development, and especially support, from the material and the lighting, by Yichen Zhou. (The synchronicity of elements, crucial for a legitimate stage musical, is nil, and so is the impact of the scenic gestures as a result.) Plus, Pelsue’s staging of actors and set pieces tends to be uncrisp and unfocused, sans a distinct language, and his disinterest in props seems to be unhelpful.

PRESS ANNOUNCEMENTS

Here is a list of select press announcements from the past week. Each headline is clickable for more information.

• See Who’s Starring in New Musical Safety Not Guaranteed at the Signature

• Like Father Musical Will Make World Premiere at Atlanta’s Alliance

• Dirty Dancing: The Musical to Launch North American Tour in August 2026

• The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee Extends Off-Broadway

• Original Operation Mincemeat Cast Will Play One Additional Show

• Noah Pacht and More to Star in The Outsiders on Broadway

• Ben Platt & Rachel Zegler to Star in The Last Five Years at Hollywood Bowl and Radio City Music Hall

• West End Sinatra Biomusical Finds Its Ol’ Blue Eyes

• Gabrielle Beckford and Harper Miles Join Cast of SheNYC Arts World Premiere Chasing Grace

• Amas Musical Theatre to Celebrate 50th Anniversary with Bubbling Brown Sugar

• Alexandra Silber’s After Anatevka, Pop Musical Proud Marys, Florencia Iriondo’s Song Society, More Set For Ignite Concert Festival

PREVIEWS AND OPENINGS

Here is a list of the new musicals and revivals either opening or beginning previews during the upcoming week, specifically on Broadway and Off-Broadway. It contains, as well, select new musicals beginning performances regionally, and select new musicals and revivals beginning performances in New York City. Each title is clickable for more information.

Monday, February 9

Tuesday, February 10

Wednesday, February 11

• Previews: Bigfoot!

Thursday, February 12

Friday, February 13

• Previews: Blood/Love

Saturday, February 14

• Previews: Night Side Songs

• Regional: The Tale of the Gifted Prince

Sunday, February 15

• Concert: Jane Eyre

Photo of a scene from Manon! by Andrew Boyle.

Leave a comment