A journal for industry and audiences covering the past, present, and future of the musical stage.

Every Broadway show must close, and every Broadway show should close. But Dead Outlaw and Real Women Have Curves, both of which opened on April 27, will close on June 29, after only nine weeks of performances: the former in part because of story, the latter in part because of craft. And each piece is, separately and incidentally, a striking example of the frequently overlooked or disregarded difference between the same.

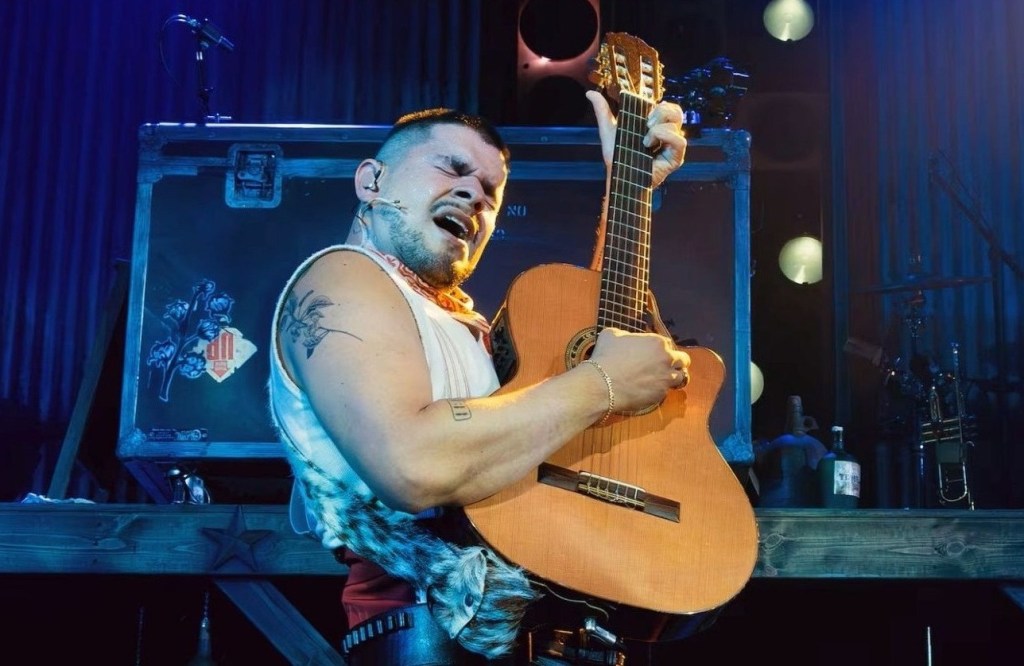

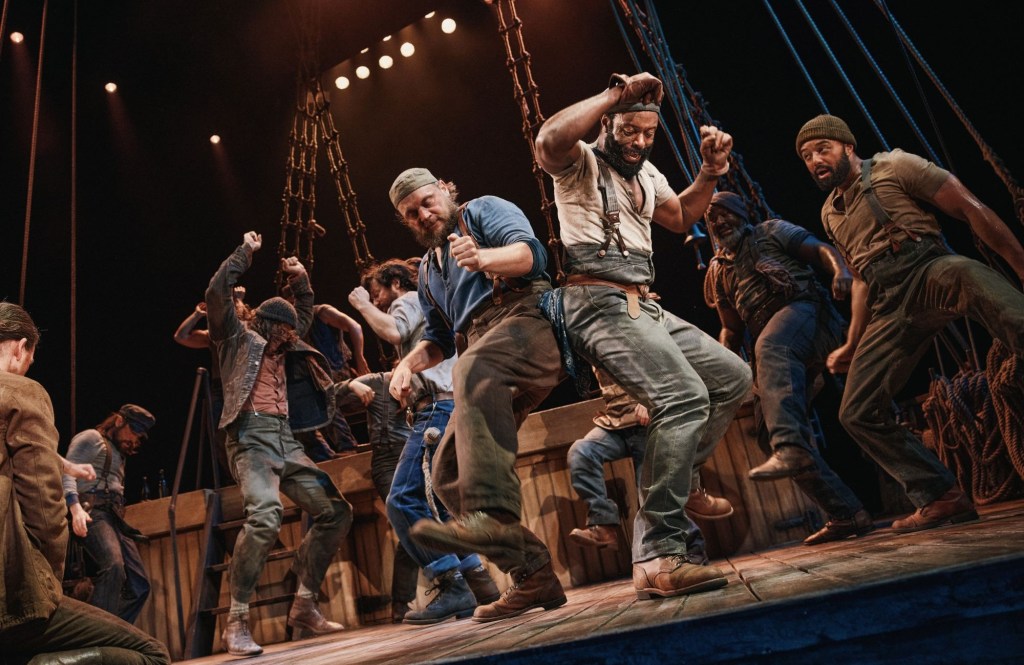

Dead Outlaw, in particular, is a tragicomic American folktale about the life and death of Elmer McCurdy. It is dark, demented, and devoid of an overtly happy ending, spanning nearly 100 years, from the late 1800s to the 1970s, and culminating with a cement truck backing into a graveyard, and it is simultaneously and undeniably one of the best written new musicals of the 21st century – a masterclass in skill and ingenuity, in the art of musical storytelling, that has been fashioned, meticulously, intelligently, and exuberantly, for the stage, exploding with theatricality and revealing an unbound rigor in the pursuit of excellence. Why, you may rightly ask, do I make such assessments? A detailed dissection of the musical and the production may be found in my original review and my reappraisal.

Dead Outlaw has been written by Itamar Moses, Erik Della Penna, and David Yazbek, with direction by David Cromer, and though its bizarre true story may not be personally appealing, Dead Outlaw should be studied by everyone who works – or seeks to work – in the musical theatre, now and in future, alongside other exceptionally well written works, like A Chorus Line (1975), Guys and Dolls (1950), Gypsy (1959), and My Fair Lady (1956), making the distinction between story and craft in the interest of understanding the art, the science, the language of the musical stage, and noting the manner in which the respective story is told, invariably marked by detail and exactitude. And Dead Outlaw should be studied not only for its material brilliance, led by an insanely intricate, insanely wonderful book, including dialogue, structure, character, and composition, but for its minor flaws, especially lyrically. The musical is a rare material feast, and let us include under the heading of material, for this discussion, the music arrangements and orchestrations of Della Penna, Yazbek, and music supervisor Dean Sharenow.

The current production of the piece should be similarly studied, but its imminent closing will likely prevent that from happening, at least on any sizable scale. Fortunately, the production has been recorded for the Theatre on Film and Tape archive at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, and the skilled, dynamic staging has, as such, been preserved. Likewise the first-rate character work of Jeb Brown, Andrew Durand, Dashiell Eaves, Julia Knitel, Ken Marks, and Thom Sesma, and the first-rate musicianship of Rebekah Bruce, JR Atkins, Spencer Cohen, Hank Heaven, and Brian Killeen.

Dead Outlaw is an extraordinary piece of theatre, and it has the capacity, under scrutiny, to be a great source of artistic inspiration, and perhaps even revivifying, as it has been for me. One may, like my husband, certainly dislike the story, or the style, but there is no denying that the musical, as carried to completion on Broadway, has been exquisitely well crafted.

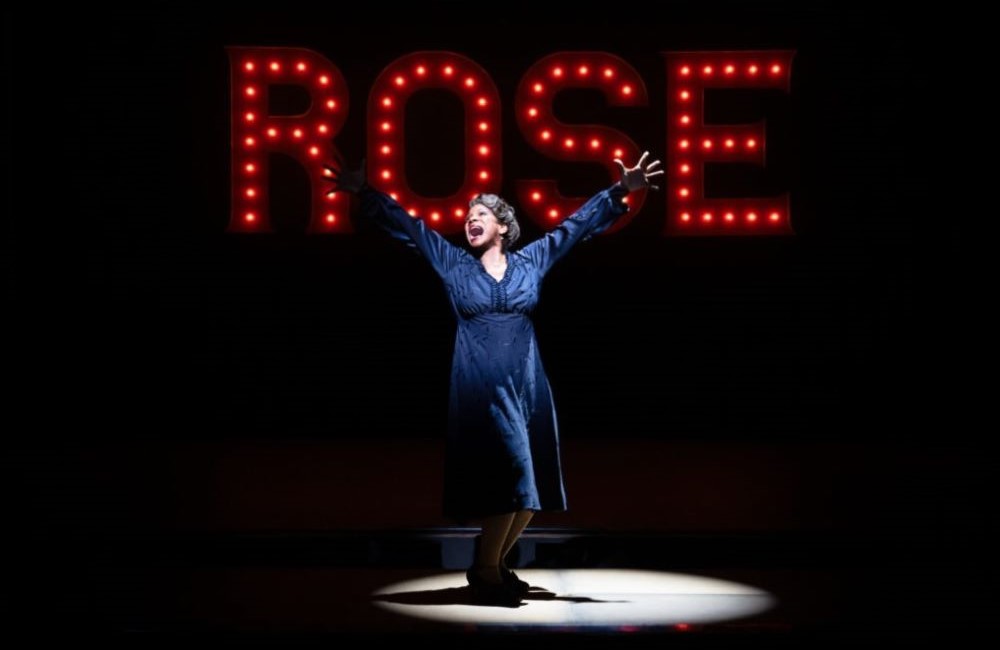

Real Women Have Curves, meanwhile, tells the story of an immigrant family living and working in Los Angeles in the 1980s. It is a disturbingly relevant, resolutely hopeful tale, complete with an ICE raid and a happy ending, that serves to humanize a marginalized community currently under attack by the American government and a faction of the American population. But, as playwright and librettist Arthur Laurents once noted, “The inclusion of an important idea (social, political, economic, etc.) unfortunately does not of itself make a play either important or good.” And Real Women Have Curves is not good. (See my review for a detailed analysis.)

The well-meaning musical, written by Lisa Loomer, Nell Benjamin, Joy Huerta, and Benjamin Valez, with direction by Sergio Trujillo, may offer the recent season’s clearest distinction between story and craft, given the timeliness and potency of the former and the low-touch presence of the latter. But the distinction between story and craft may be made in every offering, and should be made, especially when one is considering whether or not they like a musical or a production, and when seeking, as one should, to answer the corresponding question why – which is essential to the recognition and realization of excellence, lest the musical stage be confined to a perpetual state of mediocrity, its products celebrated indiscriminately. And I might add that well crafted material has never had a negative impact on the box office. The same simply cannot be said for material of the opposite sort. Or for story.

Photo of a scene from Dead Outlaw by Matthew Murphy.

Leave a reply to charlie74bfdea58c Cancel reply