A journal for industry and audiences covering the past, present, and future of the musical stage.

My Journey to Change the Mindset of an Industry and Correct the Misperceptions About an Art Form

One year ago, this week, I launched The Musical Theatre Report, and effectively began my foreseeably lengthy journey to change the mindset of an industry and correct the misperceptions about an art form, necessarily recognizing and championing artistic excellence in the process, because, as long-time theatre critic Brooks Atkinson noted in the early 1960s, “We have learned from history that the theatre will survive. But we cannot be sure it will be the free, intelligent, vital theatre that we all dream about.” And, for much of the past five decades, strictly with regard to the legitimate musical stage, it has not, despite a number of lengthy runs and a sprinkling of notable artistic endeavors. We are capable of more, we deserve more, and a theatre that is free, intelligent, and vital need not remain a dream, or confined exclusively to a collection of decades in the not-so-distant past.

We must, to that end and in my view, widen our frame of reference, and learn to differentiate between story and craft, between material and production. We must embrace the fact that the art form is not new, which does not negate the possibility of newness or invention, and we must embrace the fact that art and commerce are not mutually exclusive. We must change our approach to history and education, activating the same, and we must change our approach to awards, especially removing the elements of competition and superiority. We must abandon the false notion that there exists, in the musical theatre, some formula, fixed pattern, or definitive set of rules, and that the art form has, historically, consisted of a single homogenized sound, apparently unrelated to anything heard on the radio. We must cease the separation of musicals into arbitrary categories like “concept” vs “integrated,” understanding that the elements of every musical need be seamlessly woven together if the musical is to become a unified, theatrical whole: complete and dramatically effective. We must be measured in our language, serious in our criticism, direct and detailed in our discourse, and rigorous in our pursuit of excellence. And we must recognize that the situation in which the musical theatre, at least in America, currently finds itself, artistically, is not all that different from where it was fifty years ago, at the height of the great decline, following the decades-long movement, begun about the 1910s and brought to a close in the 1960s, to better the art of musical storytelling. (Let “we” be understood as the majority of the industry and its professional and academic pipelines.)

In 1974, for instance, author and theatre critic Walter Kerr observed, “Our theatre has become dependent upon the kindness of strangers. Once upon a time it was dependent upon the industry of our writers, men and women who sat themselves down in quiet rooms to wrestle with their creative imaginations until some sort of dramatic shape danced in the air. Then, when the dance was at last reduced to paper, actors and directors and producers came along to snatch up the sheaf and make a show of it. Today, Broadway makes its shows out of anything it can borrow, beg, purloin, or paste together.” (One descriptive size nonetheless does not fit all.)

Director and producer Harold Prince, in 1980, suggested that the “major problem” was producing. “The old money guys had taste,” he explained, “and they’d put their money where their taste was. The new money is essentially interested in more money, not the arts.” And now we are dealing with the effective incorporation of Broadway – a dangerous turn of events that some industry insiders have been warning against since the late 1990s. “Corporate thought process defining the artistic journey results in mediocrity becoming the standard,” author and director George C. Wolfe remarked at the time. “When an American musical really works, it is somehow the individual soaring. No corporate structure can duplicate that.”

But the unsteady state of the legitimate musical stage is not so simple a matter as producing, and it has persisted for such an extended period of time that Merrily We Roll Along (1981), for instance, is now suddenly looked upon as great. Even though it is not, despite a welcome air of sophistication, and if by great one means complete, well written, and dramatically effective.

Let the record show that I am brutal, frank, and unforgiving; that I will neither accept nor praise mediocrity; and that I will not refrain from directly addressing, in microscopic detail, the inadequacies or ineffectiveness of a particular piece or production. Let the record show that I will not apologize for subscribing to and endeavoring to uphold the standards of excellence in musical storytelling established in the middle of the last century. And let the record show that I stand ready and willing to embrace any new musical, like Dead Outlaw, that is well done, or, like Operation Mincemeat, whose plusses greatly outweigh its minuses. I care little about what story one wants to tell, where the idea for that story originated, what one wants to do on the musical stage; I care deeply about how one does it.

This season, I will begin reviewing new musicals out-of-town beyond the bounds of the northeast. I will continue to publish fact checks, opinions, and histories. I will aim to publish a greater number of satirical essays. And I will launch a video interview series, with a specific format and frequency to be announced. As you likely noticed, I discontinued the publication of written interviews earlier this year, and I must extend my apologies to the few individuals whose interviews were not published.

Lastly, here are some, though certainly not all, of my favorite articles from the first year of the Report – which, for me, really started to click about three months in. Let the journey continue. And let it be finite, with a free, intelligent, vital conclusion, blessed with regenerative upkeep and excepting the ongoing charge to recognize and champion excellence.

REVIEWS

• The Bedwetter at Arena Stage

• Buena Vista Social Club at the Gerald Schoenfeld Theatre

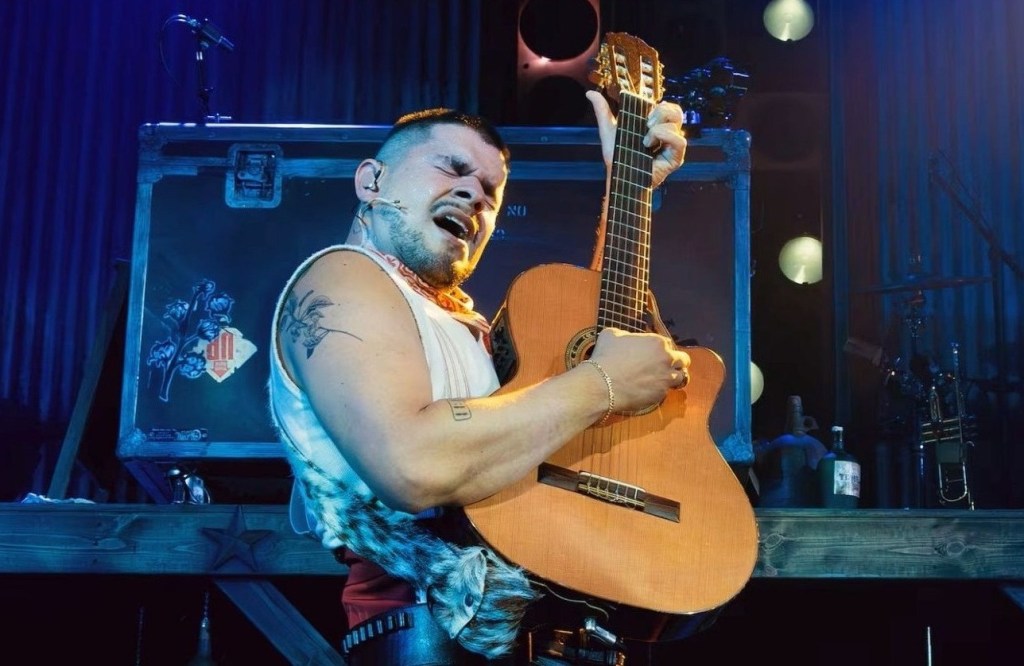

• Is Dead Outlaw One of the Best Written New Musicals of the 21st Century?

• Floyd Collins at the Vivian Beaumont Theater

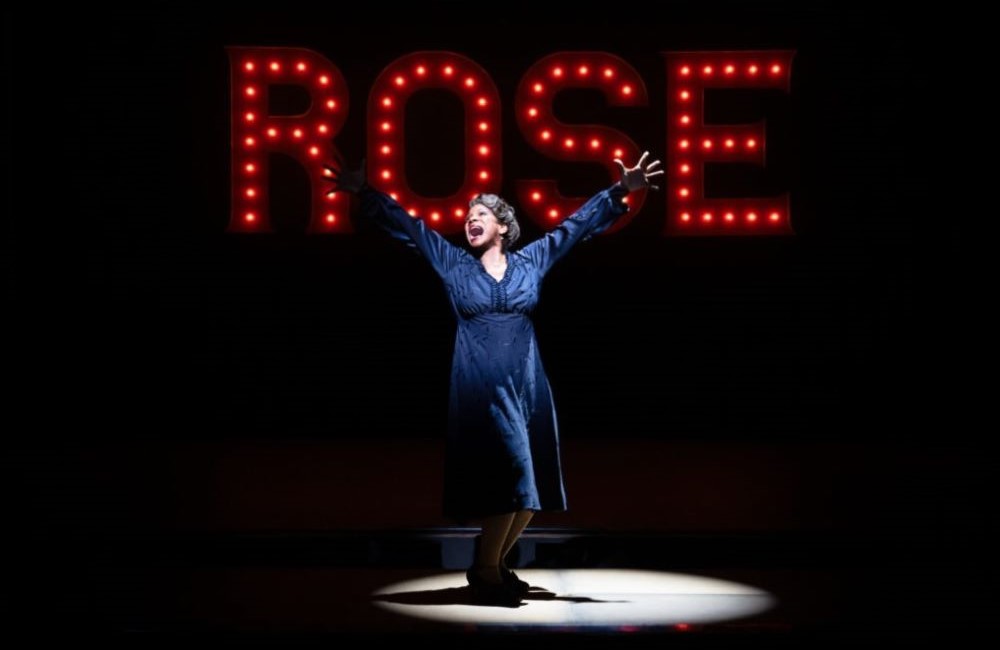

• Gypsy at the Majestic Theatre

• Maybe Happy Ending at the Belasco Theatre

• Operation Mincemeat at the John Golden Theatre

• Real Women Have Curves at the James Earl Jones Theatre

• Redwood at the Nederlander Theatre

• Senior Class at Olney Theatre Center

• Smash at the Imperial Theatre

• Stephen Sondheim’s Old Friends at the Samuel J. Friedman Theatre

• Sunset Boulevard at the St. James Theatre

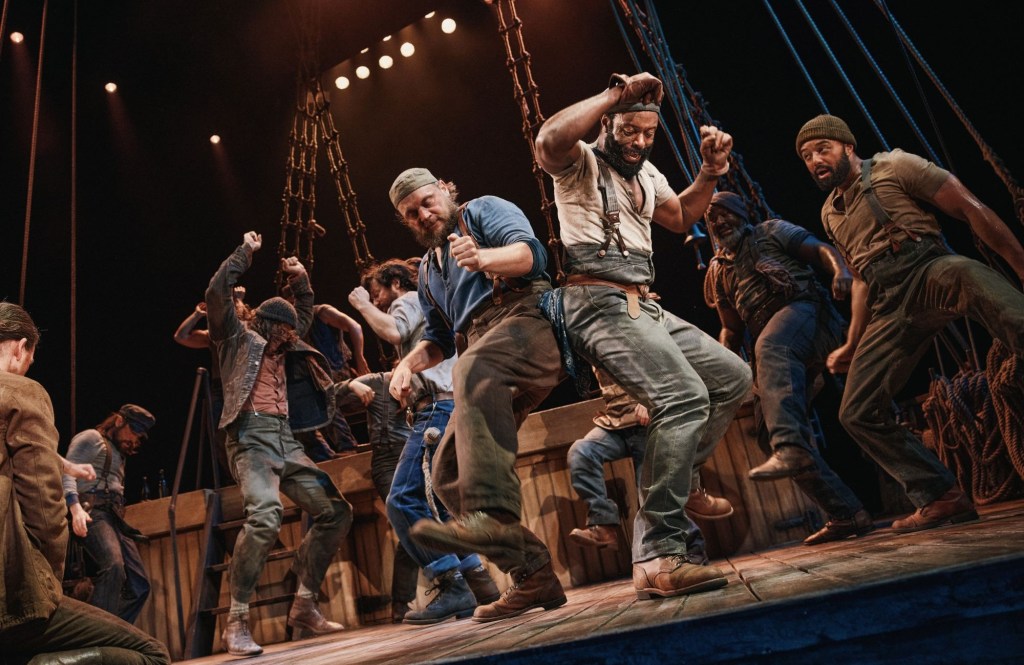

• Swept Away at the Longacre Theatre

• Take the Lead at Paper Mill Playhouse

• Two Strangers (Carry a Cake Across New York) at American Repertory Theater

• The Untitled Unauthorized Hunter S. Thompson Musical at Signature Theatre

FACT CHECK

• An Afro-Cuban Sound is Not the Same as a Story

• Audra McDonald Falsely Claims ‘We’re Not Changing a Single Solitary Line in Gypsy’

• Buena Vista Social Club: “Real Thing” or “Broadway Musical”

• An Open Letter to Moisés Kaufman (And Everyone Who Cares About the Musical Theatre)

FEATURES

• Inside the Raucous Post-Opening Ad Meeting for Buena Vista Social Club

• The 31 Rules of Musical Theatre

HISTORY

• Five Former Blackface Minstrels Who Shaped the Musical Stage

• The Flip Side of Maturity, or What Made the Middle of the 20th Century Golden?

• Is Just in Time Foolish for Opening Cold?

OPINION

• The Andrew Barth Feldman Problem, or Does Casting Now Require a Background Check?

• If Dead Outlaw Dies, Will Tony Culture Be to Blame? Plus a Reappraisal After a Second Visit

• A Kafka Musical in Kraków, or A Small Plea for Absurdity

• On the Closings of Dead Outlaw and Real Women Have Curves: Story vs Craft

• The Real Reason Swept Away Closed

• 29 Musicals and 25 Authors Beloved By a Brute, Plus 22 Extra Names That Inspire

• Six Tips for Investors and Producers (When Attending a Reading)

• Two Easy Ways to Fix the Tony Awards

• Two Promising New Musicals That Brightened the Fall Season from Beyond Times Square

• Why Every Artist and Producer Should Be Considering Revue

Photo of Andrew Durand in Dead Outlaw by Matthew Murphy.

One response

-

I don’t remember how I came across your writing here, Ben, but I am so thankful I did. I don’t always agree with your “brutal” takes (though I usually do), but I always learn from your thoughtful analyses and commentary. I very much look forward to your video interviews, and to your upcoming year’s worth of work. 👍

Leave a comment