A journal for industry and audiences covering the past, present, and future of the musical stage.

Today is Sunday, and this week’s Report features four pieces: “30 Musicals and 26 Authors Beloved By a Brute, Plus 28 Additional Names That Inspire,” “The ‘Experimentation’ with Broadway Start Times,” “Is Social Media Killing Previews? No.,” and “More Mincemeat, Less Lyrics.” Plus, a quote of the week; select press announcements from the past week; and a list of the upcoming week’s previews and openings.

QUOTE OF THE WEEK

The lyric, by Harold Rome, for “The Bunny,” from the 1942 revue Star and Garter.

Bunny, bunny, bunny

Bunny, bunny, bunny

A country maid

So sweet and fair

Was standing in

The village square.

And in her arms,

As was her habit

She carried close

A bunny rabbit.

Then a millionaire happened by,

And her little pet caught his eye.

When he offered money for her pretty little bunny,

You could hear the maiden sigh:

I will not sell it!

No, not today!

I will not sell it

Offer what you may!

How could I tell it

To go away?

I will not sell it

Don’t care what you pay!

It’s my bunny, nya, nya

Funny bunny, nya, nya

Honey bunny, nya, nya

Bonnie bunny, nya, nya

But when the right man

Comes ’round some day,

I will not sell it;

I’ll give it away.

Bunny, bunny, bunny

Bunny, bunny, bunny

Bunny, bunny, bunny

Bunny, bunny, bunny

30 MUSICALS AND 26 AUTHORS BELOVED BY A BRUTE, PLUS 28 ADDITIONAL NAMES THAT INSPIRE

Today is my birthday, and it would seem to be a fitting time for me to recognize the 30 musicals, nine book writers, and 18 songwriters who have taken up permanent residence in my heart, and who continue to fuel my love of the musical stage, plus 28 additional authors and shows who continue to inspire.

Quality, as you know, is of the utmost importance to me, for, as previously stated, I care little about what story one wants to tell, where the idea for that story originated, what one wants to do on the musical stage; I care deeply about how one does it. And, as you know, every musical must be taken and stand on its own, albeit within the context of the art form of which it is a part, and understanding the standards of excellence in musical storytelling established in the middle of the last century – not to be confused with the nonexistent rules of musical theatre.

Many of the 30 musicals listed below are incredibly well written; most are exceptional; none is necessarily flawless; and, in the case of two or three, the quality and effectiveness of certain elements are notably superior to the quality and effectiveness of other elements, and the superior elements are the forces propelling the piece across the finish line. By the same token, each of the 26 authors listed below has a body of work that is, on the whole, incredibly or exceptionally well written – though, in a few instances, I am referring only to a specific portion of their catalogue, or to a specific collaboration.

To note, the term “theatrical pop songs” refers specifically to popular songs that were written for and or popularized on the musical stage – i.e. vaudeville, burlesque, nightclubs, and legit – during roughly the first three decades of the 20th century, when the musical stage enjoyed an almost direct overlap with Tin Pan Alley. An assortment of objectively high-quality authors and shows, like Fiddler on the Roof (1964), Stephen Sondheim, and Sweeney Todd (1979), are not listed below, because they have not taken up permanent residence in my heart, nor are they among my primary sources of inspiration. No limit was placed on the number of selections. And, to be clear, not one of the below lists, whose entries are organized alphabetically, is meant to be my take on “the best.”

MUSICALS

• American Idiot (2010), by Billie Joe Armstrong, Michael Mayer, Green Day, and Tom Kitt and originally directed by Michael Mayer

• The Apple Tree (1966), by Sheldon Harnick, Jerry Bock, and Jerome Coopersmith and originally directed by Mike Nichols

• Assassins (1991), by John Weidman and Stephen Sondheim and originally directed by Jerry Zaks

• The Band’s Visit (2016), by Itamar Moses and David Yazbek and originally directed by David Cromer

• Barefoot Boy with Cheek (1947), by Max Shulman, Sylvia Dee, and Sidney Lippman and originally directed by George Abbott

• Bye Bye Birdie (1960), by Michael Stewart, Lee Adams, and Charles Strouse and originally directed by Gower Champion

• Call Me Mister (1946), by Arnold Auerbach, Arnold B. Horwitt, and Harold Rome and originally directed by Robert H. Gordon

• A Chorus Line (1975), by Michael Bennett, Nicholas Dante, James Kirkwood, Edward Kleban, and Marvin Hamlisch and originally directed by Michael Bennett

• Company (1970), by George Furth and Stephen Sondheim and originally directed by Harold Prince

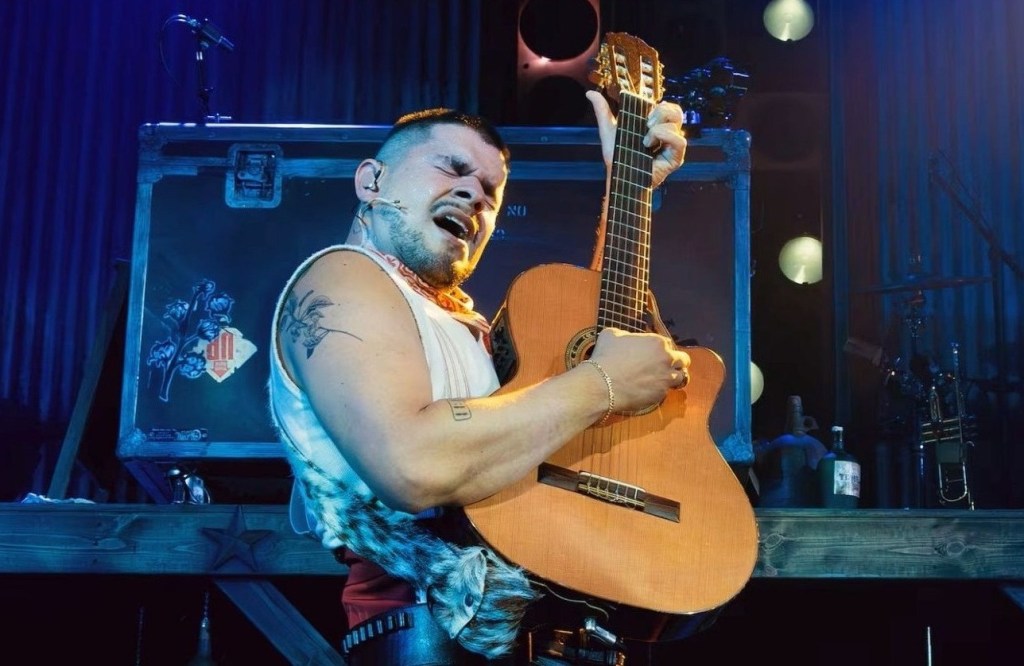

• Dead Outlaw (2025), by Itamar Moses, Erik Della Penna, and David Yazbek and originally directed by David Cromer

• Flying Colors (1932), by Howard Dietz, George S. Kaufman, Arthur Schwartz, et al. and originally directed by Howard Dietz

• A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum (1962), by Larry Gelbart, Burt Shevelove, and Stephen Sondheim and originally directed by George Abbott

• Guys and Dolls (1950), by Abe Burrows and Frank Loesser and originally directed by George S. Kaufman

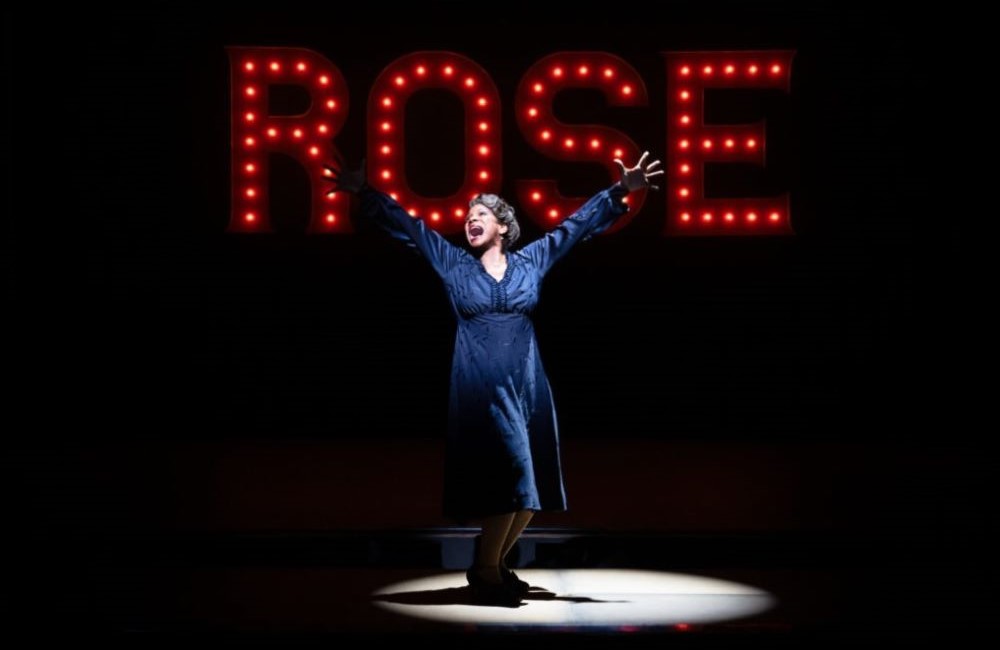

• Gypsy (1959), by Arthur Laurents, Stephen Sondheim, and Jule Styne and originally directed by Jerome Robbins

• Hello, Dolly! (1964), by Michael Stewart, Jerry Herman, and Bob Merrill and originally directed by Gower Champion

• How to Succeed in Business without Really Trying (1961), by Abe Burrows and Frank Loesser and originally directed by Abe Burrows

• Jelly’s Last Jam (1992), by George C. Wolfe, Susan Birkenhead, Jelly Roll Morton, and Luther Henderson and originally directed by George C. Wolfe

• The King and I (1951), by Oscar Hammerstein II and Richard Rodgers and originally directed by John Van Druten

• Lady in the Dark (1941), by Moss Hart, Ira Gershwin, and Kurt Weill and originally directed by Moss Hart and Hassard Short

• Little Me (1962), by Neil Simon, Carolyn Leigh, and Cy Coleman and originally directed by Cy Feuer and Bob Fosse

• A Little Night Music (1973), by Hugh Wheeler and Stephen Sondheim and originally directed by Harold Prince

• The Little Show (1929), by Howard Dietz, George S. Kaufman, Arthur Schwartz, et al. and originally staged by Danny Dare, Alexander Leftwich, and Clifton Webb under the supervision of Dwight Deere Wiman

• Matilda (2013), by Dennis Kelly and Tim Minchin and originally directed by Matthew Warchus

• My Fair Lady (1956), by Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Loewe and originally directed by Moss Hart

• No, No, Nanette (1971), by Burt Shevelove, Otto Harbach, Frank Mandel, Irving Caesar, and Vincent Youmans and originally directed by Burt Shevelove

• Of Thee I Sing (1931), by George S. Kaufman, Morrie Ryskind, Ira Gershwin, and George Gershwin and originally directed by George S. Kaufman

• Passing Strange (2007), by Stew and Heidi Rodewald and originally directed by Annie Dorsen

• She Loves Me (1963), by Joe Masteroff, Sheldon Harnick, and Jerry Bock and originally directed by Harold Prince

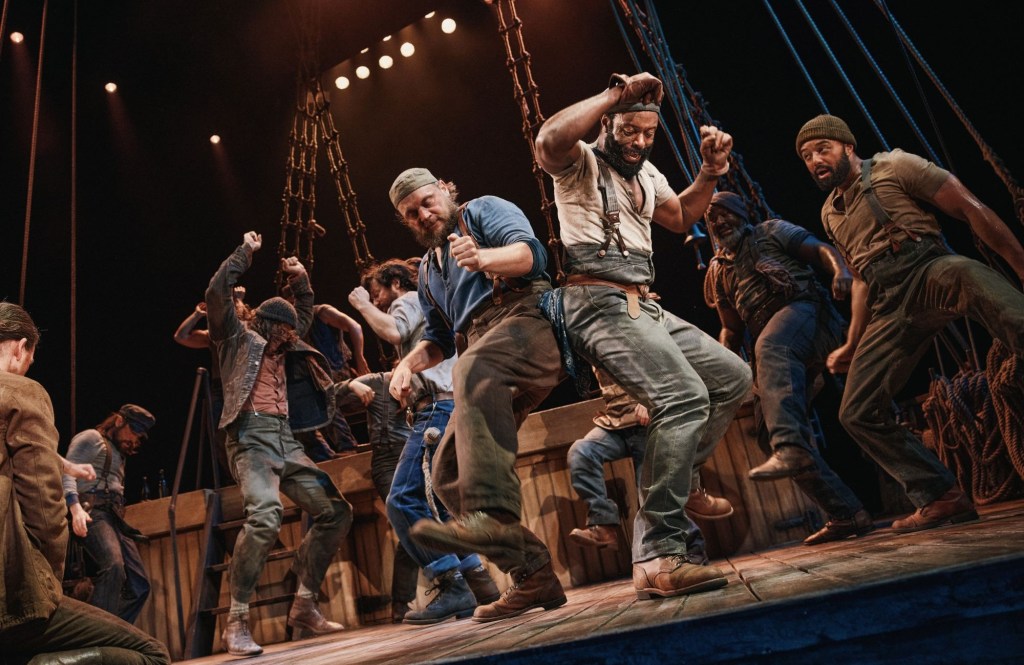

• Show Boat (1927), by Oscar Hammerstein II and Jerome Kern and originally directed by Zeke Colvan and Oscar Hammerstein II

• Three’s a Crowd (1930), by Howard Dietz, Corey Ford, Arthur Schwartz, et al. and originally directed by Hassard Short

Other musical properties of which I am especially fond include but are not necessarily limited to Chicago (1975), Fun Home (2013), Hamilton (2015), Little Shop of Horrors (1982), Parade (1998), Pins and Needles (1937), 1776 (1969), and Wonderful Town (1953). Two early, necessarily immature properties that nonetheless make me giddy over the prospects of what might have been, had they been written a couple of decades later, are Jim Jam Jems (1920) and Peggy-Ann (1926).

BOOK WRITERS

• Abe Burrows, author and or director of Guys and Dolls (1950), How to Succeed in Business without Really Trying (1961), Say, Darling (1958), et al.

• Howard Dietz, specifically as the creator and author of revues, like The Band Wagon (1931), Flying Colors (1932), The Little Show (1929), Merry-Go-Round (1927), and Three’s a Crowd (1930)

• Larry Gelbart, author of City of Angels (1989), A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum (1962), Like Jazz (2003), et al.

• Oscar Hammerstein II, author of Carmen Jones (1943), Carousel (1945), The King and I (1951), Oklahoma! (1943), Rainbow (1928), Rose-Marie (1924), Show Boat (1927), South Pacific (1949), Sunny (1925), et al.

• Moss Hart, author and or director of As Thousands Cheer (1933), Camelot (1960), Face the Music (1932), The Great Waltz (1934), Inside U.S.A. (1948), Lady in the Dark (1941), My Fair Lady (1956), et al.

• George S. Kaufman, author and or director of Animal Crackers (1928), The Band Wagon (1931), The Coconuts (1925), Flying Colors (1932), Guys and Dolls (1950), The Little Show (1929), Of Thee I Sing (1931), et al.

• Itamar Moses, author of The Band’s Visit (2016), Dead Outlaw (2025), The Fortress of Solitude (2014), Nobody Loves You (2013), et al.

• Michael Stewart, author of Bye Bye Birdie (1960), Carnival (1961), Hello, Dolly! (1964), I Love My Wife (1977), Mack and Mabel (1974), et al.

• Peter Stone, author of Grand Hotel (1989), My One and Only (1983), 1776 (1969), Skyscraper (1965), Titanic (1997), et al.

Other book writers of whom I am especially fond include but are not necessarily limited to Nick Blaemire (Safety Not Guaranteed, Soon), Hugh Wheeler (A Little Night Music, Sweeney Todd), and George C. Wolfe (Bring in ‘Da Noise, Bring in ‘Da Funk, Jelly’s Last Jam, Shuffle Along, or The Making of the Musical Sensation of 1921 and All That Followed).

LYRICISTS AND COMPOSERS

• Irving Berlin, specifically as the composer of theatrical pop songs, like “Alexander’s Ragtime Band,” and of musicals, like Annie Get Your Gun (1946), As Thousands Cheer (1933), Call Me Madam (1950), Face the Music (1932), Louisiana Purchase (1940), and This is the Army (1942)

• Jason Robert Brown, lyricist and composer of The Bridges of Madison County (2014), Honeymoon in Vegas (2015), Parade (1998), 13 (2008), et al.

• Lew Brown, lyricist of theatrical pop songs, like “Hocus Pocus,” “I’ve Got the Yes! We Have No Banana Blues,” and “Oh! By Jingo,” and of musicals, like Follow Thru (1929), George White’s Scandals (1925, 1926, 1928, 1931), Good News (1927), Strike Me Pink (1933), and a Casino de Paree revue

• Cy Coleman, composer of City of Angels (1989), I Love My Wife (1977), The Life (1997), Like Jazz (2003), Little Me (1962), Sweet Charity (1966), Wildcat (1960), The Will Rogers Follies (1991), et al.

• Henry Creamer, lyricist of theatrical pop songs, like “After You’ve Gone,” “Dear Old Southland,” “Goodbye Alexander,” “I’m Wild About Moonshine,” “Lock and Key,” “Strut Miss Lizzie,” “Walk, Jennie, Walk!,” “Way Down Yonder in New Orleans,” and “Wide Pants Willie (Rah! Rah! Rah!),” and of musicals, like Ebony Nights (1921) and Strut Miss Lizzie (1922)

• Howard Dietz and Arthur Schwartz, specifically as the lyricist and composer of revues, like At Home Abroad (1935), The Band Wagon (1931), Flying Colors (1932), The Little Show (1929), and Three’s a Crowd (1930)

• Sammy Fain, specifically as the composer of theatrical pop songs, like “If I Give Up the Saxophone, Will You Come Back to Me?,” and of revues, like Boys and Girls Together (1940), George White’s Scandals (1939), Hellzapoppin’ (1938), and Sons o’ Fun (1941)

• E.Y. Harburg, lyricist of Americana (1932), Finian’s Rainbow (1947), Hooray for What! (1937), Jamaica (1957), Life Begins at 8:40 (1934), Walk a Little Faster (1932), et al.

• Sheldon Harnick and Jerry Bock, lyricist and composer of The Apple Tree (1966), Fiddler on the Roof (1964), Fiorello! (1959), She Loves Me (1963), et al.

• Carolyn Leigh, lyricist of Hellzapoppin’ (1976), How Now, Dow Jones (1967), Little Me (1962), Peter Pan (1954), Smile (1983), Wildcat (1960), et al.

• Jimmie V. Monaco, specifically as the composer of theatrical pop songs, like “Ah-Ha!,” “Cross-Word Mamma You Puzzle Me (But Papa’s Gonna Figure You Out),” “I Love Her (Oh! Oh! Oh!),” “They Had to Swim Back to Shore,” “While They Were Dancing Around,” and “You Made Me Love You”

• Harold Rome, specifically as the lyricist and composer of revues, like Call Me Mister (1946), Lunchtime Follies (1942), Pins and Needles (1937), Pretty Penny (1949), Sing Out the News (1938), and Stars and Gripes (1943)

• Jule Styne, composer of Bells Are Ringing (1956), Do Re Mi (1960), Fade Out – Fade In (1964), Funny Girl (1964), Gypsy (1959), Say, Darling (1958), Subways Are for Sleeping (1961), Two on the Aisle (1951), et al.

• Kurt Weill, composer of Knickerbocker Holiday (1938), Lady in the Dark (1941), Lost in the Stars (1949), Love Life (1948), One Touch of Venus (1943), Street Scene (1947), The Threepenny Opera (1928), et al.

• David Yazbek, lyricist and composer of The Band’s Visit (2016), Dead Outlaw (2025), Dirty Rotten Scoundrels (2005), The Full Monty (2000), Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown (2010), et al.

• Vincent Youmans, composer of Great Day (1929), Hit the Deck (1927), No, No, Nanette (1925), Rainbow (1928), Take a Chance (1932), Through the Years (1932), Two Little Girls in Blue (1921), Wildflower (1923), et al.

Other songwriters of whom I am especially fond include but are not necessarily limited to composer Leonard Bernstein (West Side Story, Wonderful Town), composer Will Marion Cook (Clorindy, In Dahomey), lyricist and composer Dorothy Fields and Jimmy McHugh (Blackbirds of 1928, The International Revue), composer James F. Hanley (Thumbs Up!, “Second Hand Rose”), lyricist and composer Bert Kalmar and Harry Ruby (The Ramblers, “Who’s Sorry Now?”), lyricist and composer Frank Loesser (Guys and Dolls, How to Succeed in Business without Really Trying), lyricist and composer Joshua Schmidt (Adding Machine, Midwestern Gothic), and lyricist Jack Yellen (“Big Bad Bill (Is Sweet William Now),” “Louisville Lou”).

I am, likewise, especially fond of four directors who were instrumental in shaping the material for their shows: George Abbott (Damn Yankees, A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, On the Town, Pal Joey, Wonderful Town), Gower Champion (Bye Bye Birdie, Carnival, Hello, Dolly!), Jerome Robbins (Fiddler on the Roof, Gypsy, West Side Story), and Hassard Short (As Thousands Cheer, The Band Wagon, Lady in the Dark, Three’s a Crowd).

And I am especially fond of author, director, producer, and actor Bob Cole, though his lines and lyrics are necessarily immature and largely unperformable, in earnest, today, simply given the time at which they were written, circa 1900.

MORE MINCEMEAT, LESS LYRICS

Last night, I made a second trip to Operation Mincemeat, specifically to see the original cast of five before their February 22 departure, but three of the five, including the stellar Natasha Hodgson, who knows how to charge a scene, were absent, and their absence was especially noticeable in the first act, accented with laxness, poor diction, and muddled sound. (A real disappointment.) Even a nearby stranger who had already seen the show numerous times confessed to having trouble understanding the lyrics. (The authors’ heavy use of lightning-fast rhythmic patter has its dangers, as I noted in my original review.)

Otherwise, the plusses, in material and production, remain. The minuses, in material and production, remain. And Zoë Roberts continues to give an extraordinary performance, particularly in her roles as Johnny Bevan, Ian Fleming, and a sweaty consulate official in Spain.

And revisiting the piece has marginally increased the appreciation I already had for the work of choreographer Jenny Arnold and director Robert Hastie, whose production is slick, classy, and quite fine – though certainly not flawless. Hastie has a firm grip on the stage and the story, and, for most of the show, he moves his actors about the stage, in the service of the story, with precision and purpose. Note, in particular, how he motivates something so seemingly simple as a cross that takes a seasoned secretary stage right for her moment in the spotlight, surrounded by a blue wash, steadily gaining in intensity. (Mark Henderson designed the lighting.) Hastie does well, on the whole, executing the transitions, buttons, and bumps: unifying the active elements, and ensuring the staging remains, by and large, tight and propellant. (The button of “Useful” is still sensational.) And he does well, on the whole, utilizing the tricked-out war-room of a set, sustaining, by and large, physical balance and visual interest, with modest invention.

Lastly, a word must be said for the exceptional costume design by Ben Stones. It is sharp and chic, and it does a stupendous job of delineating the different characters, and defining the world of the show. The five primary outfits are wonderfully dapper and wonderfully adaptable – an individualized combination of suit pants, dress pants, shirts, and blouses, with pinstripes, suspenders, glasses, suit coats, and ties of different lengths. And the myriad accessories are divine: white jackets, black jackets, tan jackets, a navy naval overcoat, lab coats accented with neon edging, white jackets accented with red collars and cuffs, black smocks splashed with glittery red blood, a brown bomber jacket with an imprint of the American flag, metallic vests, sweaters, trick sleeves with rainbow ruffles, newsboy caps, straw fedoras, masks, gloves, hankies, and so forth, in several instances providing the actors with tangible, playable pieces they might incorporate into their characterizations.

THE “EXPERIMENTATION” WITH BROADWAY START TIMES

Tim Teeman, of The Daily Beast, recently wrote a lengthy piece, for The Hat, exploring the current “experimentation” with Broadway start times. The piece focuses especially on the upcoming Roundabout Theatre Company revival of The Rocky Horror Show, whose performances will commence, depending upon the date, at 2pm, 3pm, 3:30pm, 4pm, 5pm, 7pm, 8pm, 8:30pm, 9pm, and 10pm. The production’s director, Sam Pinkleton, suggests that the start times for The Rocky Horror Show, particularly the later start times, are “unheard of on Broadway,” adding that he longs for a midnight show. And he suggests that the “rules” about performance schedules are “one of many arbitrary things about the system.” (What are the others?)

I agree with Pinkleton, to the extent that each producer should design a performance schedule that best suits the needs and nature of their respective show, and, in the interest of supporting, perhaps even enhancing Pinkleton’s argument in favor of “weird” start times, I must correct him on two points. First, no “rules” exist, in principle, with regard to performance schedules, though one must necessarily take into account certain union matters, like turnaround time and eight performances constituting a week – a matter that was solidified in 1919, courtesy of an Actors’ Equity strike. And second, Broadway has, historically, seen an array of start times. Those of The Rocky Horror Show are neither new nor experimental.

In 1914, for instance, Dancing Around played matinees at 2pm and evenings at 8pm. The Girl from Utah played at 2:10pm and 8:10pm. Ziegfeld Follies played at 2:15pm and 8:15pm. And The Passing Show played matinees on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays.

In 1920, Cinderella on Broadway played at 2pm and 8pm. Poor Little Ritz Girl played at 2:15pm and 8:15pm. The Night Boat played at 2:20pm and 8:20pm. Irene played at 2:30pm and 8:30pm. And Mary played matinees on Wednesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays.

In the 1920s, a dozen or so Black musicals played a weekly midnight show. Among them were Blackbirds of 1928, Dixie to Broadway, Messin’ Around, and Shuffle Along. Pleasure Bound, a Shubert entertainment with a white cast, briefly instituted a weekly midnight show. And some midnight shows commenced at 11:30pm or 11:45pm.

In 1933, Face the Music played at 2:30pm and 8:30pm. Of Thee I Sing played at 2:35pm and 8:35pm. Walk a Little Faster played at 2:45pm and 8:45pm. And Pardon My English played matinees on Wednesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays.

Incidentally, no play or musical was allowed to be performed on Sundays until 1935, when a pair of bills, several years in the making, passed the State Legislature, freeing the legitimate New York stage from long-standing Blue Laws. The passage of these bills, sponsored by Senator Julius S. Berg, of the Bronx, occurred, not coincidentally, at a precarious time for the theatrical stage, against the backdrop of the Great Depression and the boom in radio and talking pictures. Henry Moskowitz, the executive adviser of the League of New York Theatres, founded in 1930 and now known as the Broadway League, remarked, upon the passage of the bills, “From the standpoint of the legitimate theatre, I do not claim that this measure is the sole solution of its ills. The legitimate theatre is so badly battered that anything which can be done to help it economically should be done. The theatre can now draw upon audiences which do not attend it on week days and with proper exploitation new audiences will be found. I am looking forward to Sunday shows at reasonable prices so that the working people will be brought back to the legitimate theatre. It is too great an asset to be just a Park Avenue annex.”

In 1942, Let’s Face It! played at 2:30pm and 8:30pm. Lady in the Dark played at 2:35pm and 8:35pm. Best Foot Forward played at 2:40pm and 8:40pm. And Keep ‘Em Laughing and Priorities played, daily, at 2:30pm and 8:30pm, with an extra 5:30pm show on Saturdays and Sundays. These two offerings brought vaudeville to the legitimate stage under the banner of revue, in a relatively minor trend that emerged in the early 1930s, peaked during the Second World War, and coincided, not coincidentally, with vaudeville’s institutional demise, in the early 1930s.

Elsewhere, in 1942, Wine, Women, and Song played, daily, at 2:30pm and 8:40pm, with an extra midnight show on Saturdays and an extra 5:30pm show on Sundays. The musical, headlined by Margie Hart, joined a couple of other musicals, like Star and Garter, headlined by Gypsy Rose Lee, in bringing strip-house burlesque to the legitimate stage under the banner of revue, spurred on by the closing, that year, of the town’s temples of sin, due to the refusal of Mayor Fiorello La Guardia and License Commissioner Paul Moss to reissue the necessary permits. Wine, Women, and Song was shut down by the government ten weeks into its run, with its producer, I.H. Herk, simultaneously sentenced to jail.

Prior to the 1930s, burlesque was a style of entertainment and a form of entertainment, characterized, in both cases, primarily by slapstick, travesty, and knockabout comedy, not striptease. And burlesque was a part of Broadway. And vaudeville was a part of Broadway. And, between the 1910s and the 1940s, nightclubs were an integral part of Broadway, with many or most presenting theatrical entertainments – which had an assortment of start times, ranging from roughly 8pm to 2am, depending upon the resort.

In the 1950s and 60s, 8:30pm would prove to be an especially popular start time, though Buck White played Saturdays at 7pm and 10pm; and, in the 1970s, 7:30pm would prove to be an especially popular start time, though You’re a Good Man, Charlie Brown played on Sundays at 5pm in lieu of a Monday or Tuesday performance. The 1999 revival of You’re a Good Man, Charlie Brown played Thursdays at 2pm and 7:30pm, Fridays at 7:30pm, Saturdays at 11am, 3:30pm, and 8pm, and Sundays at 1:30pm and 6pm. And the 2000 revival of The Rocky Horror Show played Tuesdays through Fridays at 8pm, Saturdays at 5pm and 9:45pm, and Sundays at 2pm and 7pm.

A single Broadway performance schedule does not necessarily serve the best interests of every show. (Nor necessarily does eight performances constituting a week.) And I hope that Pinkleton gets the midnight show for which he longs. Still, one can surely appreciate the popularity and practicality of the window between seven o’clock and nine o’clock – which nonetheless has 121 minutes from which to choose. And one must simultaneously concede that “weird” start times, at a certain point, become little more than futile pandering, for a bad show is a bad show, whether one sees it at eight o’clock or 6:15, and a great show is likely to attract an audience whenever it runs, within reason. And thus we return to that ever-present matter of quality.

IS SOCIAL MEDIA KILLING PREVIEWS? NO.

The Queen of Versailles was a commercial failure, and some attribute its unfortunate outcome, at least in part, to the savagery spewed forth on social media during previews. (I do not read or contribute to online forums, so I do not have first-hand knowledge of what was said.) One general manager, unaffiliated with the show, has even suggested that Broadway previews are not “built for the speed of the internet.” But that is hogwash.

First, the chatterati have been bludgeoning new musicals for decades. City of Angels (1989), for instance, was, during previews, “marked as a sure failure by virtually everyone in the New York theatre,” and it wound up running two years; and Street Scene (1947) received a largely rhapsodic reception, even though, as Oscar Hammerstein II wrote in a letter to its composer, Kurt Weill, “everyone in town had closed the show before it opened.” A musical with artistic merit – moderate, considerable, great, or supreme – is almost certain to overcome any preliminary torment inflicted upon it by cacophonous third parties – which, in any case, does not guarantee commercial success; it merely increases the chances of achieving the same.

Second, several new musicals, like The Queen of Versailles, are now recording their Broadway cast albums prior to the start of previews – which suggests that the producers and the creative team feel that the piece is no longer in need of work. So, how can one be up in arms over the chatterati making comments during previews about a piece that is evidently no longer in need of work?

And third, the preview period, on Broadway, is for refinements, for tightening, for finetuning, not for wholesale rewrites. Any individual who perceives said period as a time to fundamentally retool their musical is taking a tremendous – and tremendously foolish – risk, and their musical is virtually guaranteed to retain, at the end of said period, whatever artistic deficiencies it might have had at the beginning, perhaps even acquiring more along the way.

Hearing a musical performed aloud and seeing a musical staged are critical to understanding what works and what does not work – thus the reason for readings, workshops, and pre-Broadway engagements. The preview period, on Broadway, is not the time, nor is Broadway the place, to begin listening, with a critical ear, to – or looking, with a critical eye, at – one’s work, nor is the preview period the time, or Broadway the place, to begin solving, in a serious and methodical fashion, issues of narrative ineffectiveness, particularly those stemming from faulty or inexpert material, and especially given the technical complexity of most current productions – which increases the difficulty of making substantial substantive changes.

Every creative team, in these days of multi-year development, should know, broadly speaking, what, if anything, is not working before the start of previews, and the team should have either hatched a plan to address such items or made the decision not to address them. (One exception might be complications that arise in rehearsal due to less-than-ideal casting.) But this, of course, assumes that the members of the team are trained in the art of musical storytelling, capable of objectivity, and honest with one another and themselves.

Bringing a musical to Broadway prematurely, specifically in an unsteady or unsatisfactory artistic state, is, in these days of multi-year development, a choice, not an accident. And neither the preview period nor the chatterati should be made to serve as scapegoats for a producer’s or a creative team’s poor choices. But an unsteady or unsatisfactory artistic state has not stopped many a musical from thriving. The risk is yours.

PRESS ANNOUNCEMENTS

Here is a list of select press announcements from the past week. Each headline is clickable for more information.

• Beth Malone, Krysta Rodriguez, Sam Gravitte, More Cast in World Premiere of Starstruck Musical

• Full Cast Announced for The Rocky Horror Show on Broadway

• Rolando Villazón to Star in Man of La Mancha at Lincoln Center Theater Gala

• Goodspeed Musicals Pauses Productions at Terris Theatre for 2026

• New Musical Cable Street Joins the Brits Off Broadway 2026 Lineup

• Operation Mincemeat Extends on Broadway for a Seventh Time

• Jersey Boys to Launch North American Tour in September 2026

• Full Cast Set for Broadway Transfer of Cats: The Jellicle Ball

• Jared Zirilli Joins Delaware U.S. Premiere Glory Ride Musical, About Tour de France Champion Gino Bartali

• All-Star, 3-Day Broadway Concert Event The Festival Set for New York’s Hudson Valley

• Masquerade Announces New Casting

• Shereen Pimentel to Lead Oklahoma! at 2026 Glimmerglass Festival

• Songs for a New World Will Be Performed as the York Theatre’s Spring Benefit

• The Outsiders Has Recouped on Broadway

• N’Kenge and Christina Sajous Will Co-Direct That’s Love! The Dorothy Dandridge Musical

• Eva Noblezada Postpones Return to Broadway’s The Great Gatsby

• Discovering Broadway Commissions Original Musical from Zack Zadek

• Grace Yoo, Emily Kuroda, Marc Oka, More Join East West Players’ Revised Flower Drum Song

PREVIEWS AND OPENINGS

Here is a list of the new musicals and revivals either opening or beginning previews during the upcoming week, specifically on Broadway and Off-Broadway. It contains, as well, select new musicals beginning performances regionally, and select new musicals and revivals beginning performances in New York City. Each title is clickable for more information.

Monday, February 2

Tuesday, February 3

Wednesday, February 4

• Regional: Complications in Sue

• Concert: High Spirits

Thursday, February 5

Friday, February 6

Saturday, February 7

Sunday, February 8

• Regional: Little Miss Perfect

Photo of a scene from Operation Mincemeat by Julieta Cervantes.

Leave a comment